Different people seem to write in different ways. Some people develop quite a detailed plan before they start writing, others have only general ideas and let the story develop as they write. I’m still learning the way that works best for me, trying out different approaches.

Whatever I do, it always starts with a core idea, something that I’m interested in exploring. The book that I’m telling you about, A Prize of Sovereigns, started with a musing about what we meant by goodness. We associate goodness with a quality of a person. I wondered then whether a bad person could do good actions, and also whether a good person could do bad actions. The book grew from there.

I didn’t set out to write a historical fantasy. In fact, the initial sketch was set in the real present world. But I soon realised that the dilemmas would be much more dramatic if the central characters were absolute rulers, whose personal decisions affected millions of people. The decision to set it historically emerged quite early on. I wrote it in the same way I wrote the second novel, but quite differently from my first novel or the one I’m currently writing. For A Prize of Sovereigns I wrote what I call a “cartoon”, a 10,000 word extended short story. I mean a cartoon in the same way that artists do simplified sketches of their final work, not in the Disney sense of the word. In the shortened version, it’s easier to sketch out the overall arc of the story.

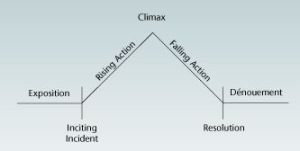

“Arc of the story” is one of those technical terms I learned. It’s really just a fancy way of saying what change happens. There are lots of ways of thinking about arcs, but the simplest is often the best – a story has to have a beginning, a middle, and an end.

In the beginning we meet the main characters (or most of them anyhow) and we see the situation they are in.

Something precipitates change, taking us into the middle of the story. In the middle, the main character encounters challenges, there is conflict, and there may be mystery or a quest. The story builds towards a climax, with dramatic reversals for the main character on the way.

In the ending, the conflicts are resolved, and any mysteries explained.

Sounds simple doesn’t it? But I recently had a short story rejected by a literary magazine for having a beginning and a middle but no end.

Anyhow, I sketched the arc of the story with my 10,000 word “cartoon” and then I elaborated it into the novel. A colleague in my writing group asked me, when I described this method of writing, whether it wasn’t boring since I knew what the ending was. Well, actually it isn’t. The cartoon really only had five main characters – two rival princes, a scheming chancellor, a peasant archer and his sweetheart. I added three more major characters as I wrote – an itinerant story-teller who rises to become a medieval spin-doctor, an abused queen who plots her revenge on her husband, and a religious girl who hears voices, telling her to save her country from invasion. The plot lines became more numerous and the weave thicker. The characters, with more interactions open to them, began to do things I hadn’t expected, and take me to places I hadn’t planned. So, no it wasn’t boring at all. It was a joy. As soldiers are fond of saying, “no plan survives the first engagement”.

Different authors seem to be very different in how they relate to their characters, but a successful character will always become partially autonomous of you. That’s the problem, or the pleasure, of being a Creator, without being omnipotent or omniscient. Sometimes they whisper their stories in your ear, sometimes you have to release them and leave them to show you what the story is.

As the tapestry of your story starts to become more complex, you’ll probably need some tools like I do. I usually develop at least a timeline to keep track of the sequence of events including backstory that isn’t fully developed in the book, and character sheets to record what I learn about my characters, so I don’t inadvertently contradict myself about their age, or appearance, or whims and habits. You can buy author software that does this and more for you, but you can do it just as easily with pencil and paper, or on a spreadsheet.

At a minimum you probably want to make sure you know and record the following things about your main characters:

- Name

- Age

- Origins (including family and background)

- Appearance

- Characteristics (positive and negative) and flaws

- Distinctive mannerisms

- Likes and dislikes

- Goals

- Key relationships

You won’t necessarily use all of these things in the writing, but you should know them, if you want to know who they are and how they might react in the situations that develop.