I’ve read a lot of stories recently, as part of sifting submissions to Freeze Frame Fiction. Many are okay. They have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But the memory of them blows away in the wind. I reject around 99% of the submission, and I’m becoming aware that the stories that give me pleasure have a quality which I’ll call density.

Perhaps I can best explain what this quality is by describing yarns that don’t have it. There is a character. He or she has a problem. As they try to solve the dilemma other characters help or frustrate them. There is a final resolution. So we have a general storyline. And some tales don’t go further. The writing is only one layer thick.

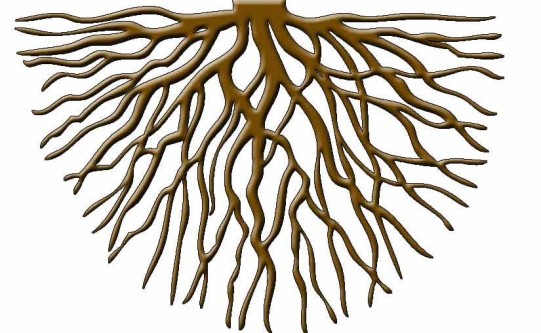

More satisfying stories are multi-layered. They have a past. Like geological strata, they speak of deep forces. The surface layer is the simple storyline—what the protagonist wants and what happens to him or her. But below the skin may be layers that are shaped by the protagonist’s identity and world they inhabit. These strata create subplots. Perhaps what the protagonist wants is not what they really need. Perhaps their station in life or the times into which they’re thrust constrain what they can do. And so, the storyline is supported by an underpinning of other meanings.

Density is the connection between things and the way events and places and objects resonate with each other. This is inherently satisfying to a reader because we respond to worlds that are saturated in meaning. Narratives lacking density feel insubstantial as candyfloss.

Stories are powerful not because they are a chain of events, but because they show us connections. They tell us what goes with what, what is important and what’s unimportant, who to praise and who to blame. They’re not just about what happened, but about what those happenings mean.

A sense of density can be fashioned in many ways.

- The way a plot embodies a bigger issue or message

- Layers. The structural element of density is created by adding layers or subplots

- Motifs. These are recurring ideas or images which resonate with each other and create a satisfying experience of connectedness. This is partly achieved by structure and partly by wordcraft.

An example

I wrote a 100-word flash fiction story, called Short Circuit, about a monk in a medieval scriptorium. His task is to scribe an illuminated manuscript. As the sun’s rays reflect off the gold leaf, he has a revelation. He believes the words on his page picked out by the sun are a message–meaning is created by a short circuit of the manuscript.

The story went through 16 drafts, growing to 2,066 words. In the second draft, I added a Viking attack just at the moment of revelation. In subsequent edits, I gave the monk an interest in researching the alchemical skills of the ancients, a passion that flirts with heresy. There was now an obvious theme of the conflict between knowledge and spiritual authority. Quite intentionally I began to craft this to echo modern debates about truth and its denial. The metaphor of fire was coming to play a major role—the fire of insight and the fire of pillage. I decided that the abbey was on the holy isle of Lindisfarne at the time of first Viking raid in 793.

And that led me to the monk’s backstory. He had been an apprentice blacksmith before a local chief slew his parents. Iron can make tools, but it also makes weapons, and the boy abandons iron in a quest for tranquillity and learning. Under attack from the raiders, the monk turns back to his cell to save a valuable letter from a correspondent in Byzantium.

The ending remained elusive. Again, I returned to blacksmithing for the answer. The monk reinterprets the words picked out by the sun to mean he is commanded to be the destroyer of the invaders. Breaking his vows, he takes up the iron again, seizing a weapon.

How to use the concept of density

The elements below roughly correspond to stages in the writing process

- The seed of the story. This is the writer’s animating purpose. It may be an idea you want to explore, a situation, a moral, a dilemma–stories can emerge from anywhere. Note, this is not the same as the basic storyline. Give the seed time to put out roots before you start drafting. My story, Short Circuit, originated from a comment by a writer arguing the literary meaning is a short circuiting of the world.

- The chess board. This is where the storyline exists. There is a location and a cast of characters, a set of pieces that move in distinct ways. At the beginning, you may not know exactly what they will do. You may discover this as you let them interact. My chess board for Short Circuit was the Viking interruption of the monks’ life in Lindisfarne Abbey. The protagonist has conflicts with the Prior about his pursuit of knowledge, and an inner conflict about the brutal killing of his family.

- The mountain. Beyond the moving, mating and slaying on the chess board, there’s an over-arching destination, the distant mountain. This may only come into view slowly for you as you write. In Short Circuit, the monk puts his own life in danger to save the valuable letter. He puts his soul in jeopardy by taking up the sword.

Everything that happens on the chess board should move the story closer to the mountain. The mountain is both the resolution of the story and the achievement of the writer’s animating purpose. It is the fruit of the gambits on the board and of the seed’s flowering.

- Polishing in the infinite hall of mirrors. This is possible only when you’ve completed the first draft of the story. It’s part of the editing process. In that process, you check for comprehension, flow, clarity, coherence. Often, the first draft is just the bare bones of the story. Now you tighten it up and make the prose sing. But the editing stage may also be where you discover what the story is about and add additional layers.

Finally, you look for ways to connect the layers, making them resonate with the same underlying meaning. Recurring motifs, reflecting each other in the hall of mirrors, help to create this effect. In Short Circuit, the recurring motifs were good iron and bad iron, good fire and bad fire.

Fine elucidation of the many steps in a writer’s process to achieve a work with depth.

I think density, the multi-layered nature of such a work, is about the most attractive quality of a good book or story. I love trying to puzzle out the author’s meaning, from description, nuance, double meanings and suggestion, as well as plot, setting and character. Your photo of the layers of rock in a cliff face illustrates the point well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much for commenting, Andy.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve read this post a couple of times, and will undoubtedly read it again. This is very helpful, Neil, as I’m working on learning the craft of writing. Especially with the examples.

Now, I’m off to read the Freeze Frame Fiction stories. Thanks for posting this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading, Brenda. It’s really good to know it was helpful.

LikeLiked by 1 person