You’ve had the experience, I’m sure, of reading a new story and thinking, “I’ve read this before.” What similarity creates this sense? In part, it’s the shape of the story arc. Some time ago, I wrote a post about the shape of stories. Stories with similar arcs can feel similar. Think of the rags-to-riches trope.

Or the “man-in-a-hole” trope of the overcoming of adversity.

Such simple diagrams give us a sense of the story arc. Other methods are available[1].

In the simple examples above, which come from Kurt Vonnegut, the shapes are made by the changes in the protagonist’s fortunes over time. And this corresponds roughly with what we mean by plot.

But what of other features of stories, irrespective of plot? For example, the personality of the lead characters, the tempo (pace) of the story, or the complexity and imagery of vocabulary? The first of these is often characteristic of series, where characters recur. The next two have more to do with the distinctive “voice” or style of an author. Might stories with similar plot arcs feel different to readers? Or might radically different plot arcs feel similar?

I decided to run a chapter from the novel I’m working on, The People of the Bull, through several text analysers. Here’s a sample of the opening:

“The day Hecta, my mechter’s mechter, died much like to any other day was. Listen and I will tell. My mechter, Serega, and Iennos, zirs brechter, the flocks tended. Hecta’s mate Arcu, my mechter’s pichter, nothing knew and in the far valleys the great tawros stalking was. Yes, ill Hecta was, but sickness common is. Most recover. But being ended and becoming arrived. The shaking sickness it was, and many in the weyk that dreadful spring, sudden as a wykwos, it carried off.”

The oddity of the language is deliberate. The story is set eight thousand years in the past, and the vocabulary and the grammar are a simulation of the language these people may have spoken: Proto-Indo-European.

None of the analytical engines commented on this oddity. The “I Write Like” engine decided, improbably, that I wrote like J.K. Rowling. Readability Formulas assessed it as readable at around fifth grade level and as having above average lexical density (measures the proportion of lexical words—nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs—to the total number of words.) and below average word diversity.

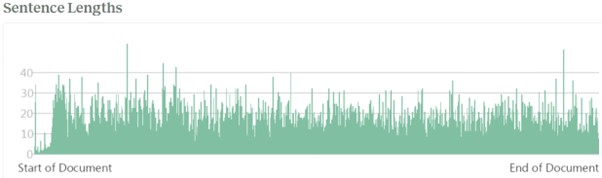

ProWritingAid is arguably one of the more sophisticate tools. It identified that words like mechter were unknown, and calculated average sentence length at 11.15 words with a good variety of lengths. For comparison, texts generally have an average sentence length of 8.2 words. J.K. Rowling’s average sentence length is 17.45 words (so, not very similar).

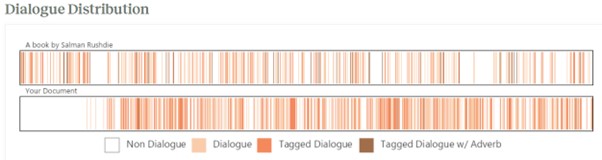

I was, perhaps, more similar to Salman Rushdie whose sentences averaged 14.95 words.

I was also significantly less dialogue rich than Rowling, but more than Rushdie.

It also scored writing style[2] as 86% and engagement at 93%. It yielded the following word cloud for the first five chapters:

The pacing shows slow paced text alternating with faster paced.

So what can tools like ProWritingAid tell us about the similarities and differences between stories? They can analyse some of the elements of the language used: are the sentences short or long? How complex are they? How much of the story is dialogue? Here is a comparison from ProWritingAid and Readability Formulas of the similarities and differences of my story with works of some other writers.

| Me | Average | J.K Rowling | Salaman Rushdie | Anthony Doerr | Bill Bryson | Zora Neale Hurson | |

| Sentence length | 11.15 words | 8.2 words | 17.45 words | 14.95 words | 11.6 words | 15.7 words | 12.95 words |

| Sentence variety | 6.7 | ? | 5.5 | 10.5 | 8.1 | 10.7 | 5.0 |

| Conjunction starts | 9.5% | 1.5% | 5.6% | 8.7% | 4.8% | 5,2% | 8.7% |

| Dialogue | 52% | 20% | 64% | 39% | 39% | 30% | 48% |

| Lexical density | 55.3% | 45% | 47.25% | 55.2% | 58.4% | 53.1% | 60.5% |

| Lexical diversity | 34.3% | 45% | 58.1% | 46.3% | 62.2% | 50.6 | 47.1% |

You can see that on none of the indicators is my writing much like that of J.K. Rowling. Most similar, overall, of the writers examined here, is Zora Neale Hurston. This may be because of her extensive use of dialect and substantial use of dialogue, but also, like me, she is prone to start sentences with a conjunction (such as “and” or “but”). Here is a sample of her writing from the opening of her wonderful book Their Eyes Were Watching God.

Ships at a distance have every man’s wish on board. For some they come in with the tide. For others they sail forever on the horizon, never out of sight, never landing until the Watcher turns his eyes away in resignation, his dreams mocked to death by Time. That is the life of men.

Now, women forget all those things they don’t want to remember, and remember everything they don’t want to forget. The dream is the truth. Then they act and do things accordingly.

So the beginning of this was a woman and she had come back from burying the dead. Not the dead of sick and ailing with friends at the pillow and the feet. She had come back from the sodden and the bloated; the sudden dead, their eyes flung wide open in judgment.

The people all saw her come because it was sundown. The sun was gone, but he had left his footprints in the sky. It was the time for sitting on porches beside the road. It was the time to hear things and talk. These sitters had been tongueless, earless, eyeless conveniences all day long. Mules and other brutes had occupied their skins. But now, the sun and the bossman were gone, so the skins felt powerful and human. They became lords of sounds and lesser things. They passed nations through their mouths. They sat in judgment.

Seeing the woman as she was made them remember the envy they had stored up from other times. So they chewed up the back parts of their minds and swallowed with relish. They made burning statements with questions, and killing tools out of laughs. It was mass cruelty. A mood come alive, Words walking without masters; walking altogether like harmony in a song.

“What she doin coming back here in dem overhalls? Can’t she find no dress to put on? – Where’s dat blue satin dress she left here in? – Where all dat money her husband took and died and left her? – What dat ole forty year ole ‘oman doin’ wid her hair swingin’ down her back lak some young gal? Where she left dat young lad of a boy she went off here wid? – Thought she was going to marry? – Where he left her? – What he done wid all her money? – Betcha he off wid some gal so young she ain’t even got no hairs – why she don’t stay in her class?”

[1] See for example topological and other approaches such as: Golizafeh et al (2018) Topological Signature of 19th Century Novelists: Persistent Homology in Text Mining Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2018, 2(4), 33; https://doi.org/10.3390/bdcc2040033; Lois Mooiman (2015) Comparing Stories with the use of Petri Nets, Bachelor Thesis, University of Amsterdam https://staff.fnwi.uva.nl/b.bredeweg/pdf/BSc/20142015/Mooiman.pdf, Anni Doshi et al (2024) Generative AI enhances individual creativity but reduces the collective diversity of novel content, Science Advances 10, 28 https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adn5290?adobe_mc=MCMID%3D51225740793224612401754393803669772565%7CMCORGID%3D242B6472541199F70A4C98A6%2540AdobeOrg%7CTS%3D1720804936#body-ref-R26 (which uses AI-supported text embedding to assess similarity between stories);

[2] This assesses elements like clarity, excessive adverb usage, hidden verbs, lengthy subordinate clauses, repeated sentence starts, excessive use of passive voice, and more.