Emily H. Wilson has performed a heroic feat of retelling in her Sumerian trilogy.

If you were setting out to retell a classic tale from the ancient world, you’d have many problems to surmount. Understanding the customs and meanings of that world would not be simple. But, more than this, you’d come to realise that what constitutes a story was also different in the olden days. There are many cultural reasons for this, but fundamentally they boil down to one thing. Fiction had not yet been invented, and, as we’ll see, would not be invented until the twelve century of the current era, at least in the West. Almost certainly, earlier stories were intended to be received as descriptions of events, as histories.

Consider what Beowulf, the Icelandic Sagas, The Iliad, and The Odyssey all have in common—they are tales of heroic deeds. There are heroes and monsters, but all these characters are “flat”. By that I mean, they have no internal life. We occasionally see their reactions to things—love, anger, grief—in between the slaying, but we don’t have access to their thoughts and feelings. And, of course, we wouldn’t if these are intended to be understood as true accounts. Everyone knows the bittersweet sadness of never being able to know what goes on in another person’s head and heart. It would therefore be absurd to pretend to know what was in Achilles’ mind or Beowulf’s. Such a conceit would break the reader’s or listener’s belief in the story. Nor was there any reason to wonder what was in the hero’s mind. It follows logically from their character. When Achilles mourns the death of Patrocles by dragging around Hector’s body—an offence to men and gods—the listener understood it as an expression of his heroic character.

Nor is there ever any doubt that Odysseus will free himself from Circe’s spell, reject her, and continue on to be reunited with his wife, Penelope. To do anything else would be a disharmony in the tale and a contradiction of his fundamental nature.

We are so used to fiction now that we don’t remark on its strangeness. To us, there is nothing remarkable about this passage from Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice:

“Darcy only smiled; and the general pause which ensued made Elizabeth tremble lest her mother should be exposing herself again. She longed to speak, but could think of nothing to say…”

Yet here we are inside Elizabeth’s mind, experiencing what she experiences, though it is betrayed by no action. For fiction to come into existence, with its pretence that we can live inside another person’s thoughts and feelings and, indeed, believe that there is anything worthy of interest in those thoughts and feelings, several things have to happen.

These conditions are eloquently argued by Laura Ashe in her 2018 article The Medieval Invention of Fiction. They came together in Europe, and specifically England, in the twelfth century. There came into existence a class of people, the feudal elite. with the wealth and the leisure to become patrons of storytelling. In medieval England, this elite was educated in French, English and Latin. Before the Norman conquest, Anglo Saxon literature had cared nothing for individuals or their wants. What mattered was that the warrior held his place in the shield wall and made good on his boasts in the mead hall. Ango-Norman feudalism overturned this, celebrating the individual knight for his own sake. At the same time, theological interpretation of the nature of sin began to move from the act to consideration of the intention. This opened the way to interest in the interior life and a consideration of selfhood. Selfhood, Ashe points out, is not yet individuality, and the Church was, indeed, profoundly suspicious of the prideful sin of individualism. The final piece of the puzzle is the invention of “courtly love”. Note, she is not saying that love did not exist in the literature of previous ages. It did, but often as an ambivalent, or even destructive, force that distracts the hero from his duty.

Courtly love was a new thing, a new idea, carried in the songs of the troubadours. Love becomes the purpose of the knight’s actions. The duty the knight owes to his liege lord becomes metaphorically displaced to submission to his lady. Ashe writes.

“Love takes the place of the higher cause which the hero serves and yet simultaneously represents his own self-fulfilment as the ultimate goal of the narrative. Now and only now is fiction made possible, for now the individual is justified for his own sake; his achievement of self-fulfilment is enough in itself to feed narrative representation. The love-plot is fictional, for it requires attention to the inner lives of at least two distinguishable individuals and asserts that their emotional experience, in the author’s imagination, is valuable for its own sake. This is the literary paradigm which gives us the novel: access to the unknowable inner lives of others, moving through a world in which their interior experience is as significant as their exterior action.”

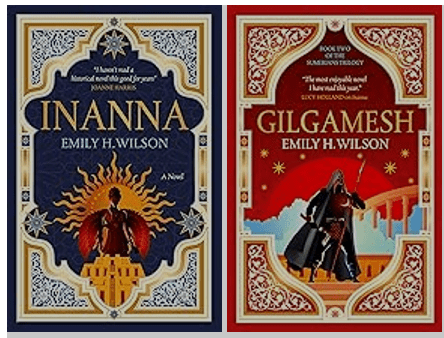

So, how now does an author retell a classic tale that is both modern and yet true to the original? The core of the problem lies in how to give interiority to the flat characters of the ancients. Emily H. Wilson faced this dilemma in writing her retelling of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. This epic is perhaps the earliest written story in the history of literature, coming down to us in cuneiform inscribed on clay tablets. Before talking about Wilson’s magnificent books (two volumes of her trilogy have now been published), let me say something about the original story.

Gilgamesh is a hero, so what he does is the work of heroes. He braves perils, he slays monsters, he treats with gods and goddesses (being two thirds god himself). The Sumerian version of the epic comes down to us in five fragmentary tales on clay tablets. The later Akkadian version collects together some of these tales and includes others. The goddess Innana makes brief appearances in this epic, and becomes central to Wilson’s retelling. Innana is a seriously cool and long-lived deity. She is not only the goddess of love, but also the goddess of war, is later known as Ishtar, and survives all the way into the classical period as Aphrodite and Venus. The relationship between Gilgamesh, King of Uruk, and Innana varies from tale to tale. In Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld Innana is Gilgamesh’s sister. By the time we get to Gilgamesh and the Bull of Heaven, she is his jealous foe, thwarted in her desire for Gilgamesh. In Wilson’s version, the two are allies and sometimes lovers, though their paths rarely cross. To be clear, it’s not that Gilgamesh lacks character. In fact, a surfeit of character is what distinguishes ancient literary figures. They do what they do because that is their character. To quote Virginia Woolf in her essay On Not Knowing Greek,

“In six pages of Proust we can find more complicated and varied emotions than in the whole of Electra. But in the Electra or in the Antigone we are impressed by something different, by something perhaps more impressive–by heroism itself, by fidelity itself. In spite of the labour and the difficulty, it is this that draws us back and back to the Greeks; the stable, the permanent, the original human being is to be found there.”

Ancient protagonists need no internal life because their motives are inscribed in their character, which, in turn, expresses archetypes rather than individual people. So Gilgamesh has emotions and traits. He starts the Epic of Gilgamesh, as a cruel and capricious ruler. The gods punish him by creating the wild man, Enkidu to humble him. The pair wrestle and Gilgamesh prevails, but they develop a bromance, setting out on adventures to prove their mettle. When Gilgamesh spurns Innana’s advances, she unleashes the Bull of Heaven against him and Enkidu. Because they slay the Bull of Heaven, one of them must die, and the gods decree the victim must be Enkidu. Gilgamesh mourns his friend, travelling into the wilderness dressed in animal skins. So far so intelligible. The proud man finds love, loses love, and is humbled by his grief. But none of this is really motivation in the modern sense. The ending of the Epic makes this clear. Gilgamesh seeks out Utnapishtim, survivor of the great flood and the only mortal men on whom the gods bestowed immorality. He wants to learn the secret of immortality. Why does he do this? Not, surely, so that his grief can endure through all the ages of Man. Rather, it’s a result of his nature: born part god, part mortal man, he seeks immortality. His quest need not be driven by any internal dialogue—it’s given in what he is.

How then does Wilson animate and flesh out Gilgamesh? Her retelling follow four main characters: Gilgamesh, Innana, Ninshubar (Innan’s vizier and a goddess herself); and Marduk (of whom more later). Wilson’s Gilgamesh is a bit of a Jack-the-lad—cheeky, cheerful, and trying his luck. But, as Wilson tells us herself, it was the desire to resuscitate Innana that motivated her. And why not, indeed? Innana is probably the great survivor among the ancient gods. Worshipped in Sumer around 4,000 BCE, she became Ishtar to the conquering Akkadians, Astarte to the Egyptians, and then Aphrodite and Venus to the Greeks and Romans. Her cult survived until around the fourth or fifth century of the current era.

Whereas Gilgamesh leaps from the page, Innana is on a slower burn, only gradually becoming herself. She starts the trilogy as a child, aware that she is the goddess of love, but not yet the goddess of war. This contradictory nature is a gift to any modern storyteller. At first, Innana is docile, sexually abused by her grandfather and then handed over as wife to an oafish husband. Relatively passive and indeed weakened after her descent into the underworld, she is dependent on Ninshubar’s help and vigilance. Only gradually does she come into herself, becoming something powerful and terrible towards the end of the second book. Ninshubar is the most exotic of the main characters, a huntress from the far south, wild and mortal-born who becomes a goddess only after being saved from death. And Marduk is the most mysterious. Pale-skinned and red-haired, he is rescued and adopted and then lost again to Ninshubar, who spends much of the first two books seeking him. He has been enslaved. But there are hints that he is much more than he seems.

It’s not all sandals and swords though. There are teasing hints of sci-fi, particularly in the underworld’s gates and the fact that it can also fly.

Gilgamesh is probably the most developed character in Wilson’s cast list. But she has other tricks up her sleeve. This is a thoroughly modern re-telling, yet it retains some of the feel of the original, with subtle nods to the Sumerian storytelling tradition. As in the original, the characters go off on quests, wandering and battling around the landscape of Sumer. And, with hints of the original, there are repeating refrains, such as Ninshubar’s “one step and then the next.”

The first book, Innana, is arguably closest to the original, incorporating several of the ancient stories. Here we get Gilgamesh’s bromance with Enkidu, and here too we get Innan’s descent into the underworld (which is the subject of a different surviving myth). The mes, which Innana steals from the god Enki in Sumerian myth, are the attributes of civilisation (positive and negative). They reappear in Wilson’s hands as mees. amulets of power. The cities and fields of ancient Sumer are there, the temples and palaces, even the smells.

By book two, Gilgamesh, great forces are in motion, devastating the lives of the humans and gods of Sumer. Sumer’s enemies overrun the city states and we learn that the gods, the Annunaki, are not the only gods in Heaven. Another, older, group of gods seek revenge on their kin. Here too, Wilson draws on antique sources, plaiting together stories that ran through Mesopotamian legend, creating a huge mythological landscape. The Enuma Elish is the earliest complete creation myth that has come down to us. In this myth, the primordial being, Tiamat, Mother of All Things, fights her grandchildren and is overthrown by her grandson, Marduk. By the end of the second of Wilson’s book, Tiamat is there and seems to have declared war on the Annunaki. My bet is that Marduk is going to slay her in the final book of the trilogy.