What is the oldest story in the world?

Stories are a miraculous technology. They tell us what is important and what unimportant, what goes with what, who to praise and who to blame. And they afford us the experience, denied in real life, of experiencing life from inside somebody else’s head. Imagine if we could excavate the stories told at the equinox within Stonehenge, or the stories told at night in the first city. Or, even, the stories we told in the mother continent of Africa before we fanned out around the world. Imagine imagining as our ancestors did!

The oldest story recorded in writing is probably the Epic of Gilgamesh, inscribed in Sumerian cuneiform around 2,000 BCE.

Writing, of course, is a fairly recent invention in the span of human history. Stories would have been transmitted orally before that innovation.

One proposed method for finding even earlier stories is to trace the ancestry of stories today. If two distinct cultures tell the same story, it might reasonably be inferred that the story must have been told by the common ancestors of both cultures. In this way, a tree of descent can be constructed, similar to evolutionary trees in biology.

The next figure shows the tree of descent from the hypothetical Proo-Indo-European language of one common story found across many modern languages of the Indo-European family created by researchers Da Silva and Tehrani[1].

The story in question is “The Smith and the Devil”.

A smith makes a pact with a malevolent being—in return for his soul, he is granted the ability to weld any materials together. The smith then tricks the devil out of his prize by sticking him to an immobile object, such as a tree or a rock. Some versions of the tale include three foolish wishes. Some end with the smith being denied entry to heaven or to hell. One version of the story is here https://vocal.media/geeks/the-devil-and-the-smith

If da Silva and Tehrani are right, this may the oldest traceable tale, going back to the Bronze age some 6.000 years ago. Naturally, there will older tales. Our ancestors must have come out of Africa tens of thousands of years ago already painting, dancing and telling stories.

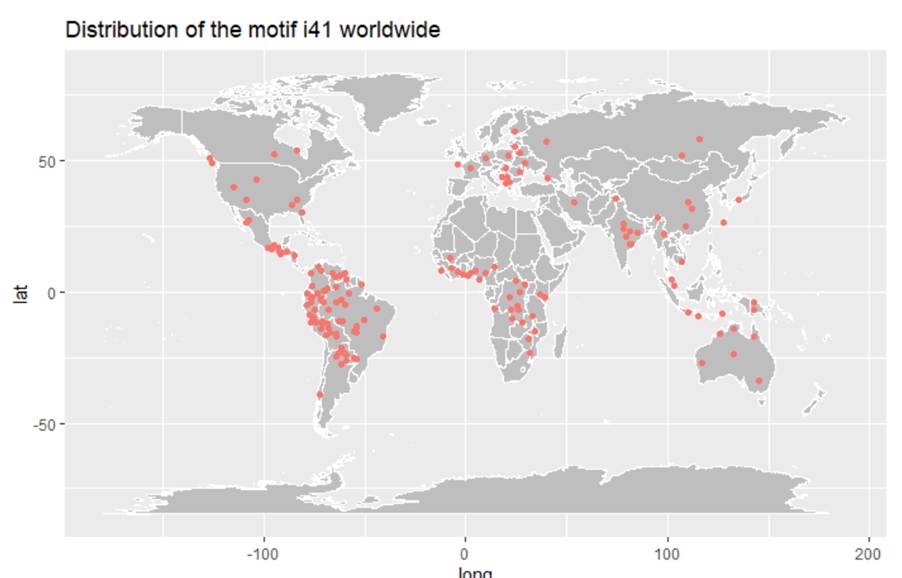

Efforts to reconstruct such tales include the rainbow serpent motif. The map below shows its distribution to be global, as described in a preprint paper that is yet to be peer reviewed.

From: Hélios Delbrassine, Massimo Mezzavilla, Leonardo Vallini, Yuri Berezkin, Eugenio Bortolini, Jamshid Tehrani, Luca Pagani Worldwide patterns in mythology echo the human expansion out of Africa https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.01.24.634692

The elements of this proto-narrative are described by Julien D’Huy in a 2016 Scientific American article[2] as follows:

“Mythological serpents guard water sources, releasing the liquid only under certain conditions. They can fly and form a rainbow. They are giants and have horns or antlers on their heads. They can produce rain and thunderstorms. Reptiles, immortal like others who shed their skin or bark and thus rejuvenate, are contrasted with mortal men and/or are considered responsible for originating death, perhaps by their bite. In this context, a person in a desperate situation gets to see how a snake or other small animal revives or cures itself or other animals. The person uses the same remedy and succeeds.”

The basic technique is borrowed from evolutionary biology: the idea is that we can track the evolution of myths and folktales with the same techniques that we use to establish evolutionary relationships and evolutionary history. The method used for the identification involves tracing stories or story motifs (mythemes) across the world.

If two distinct cultures tell a common, or related, story, there are three possible mechanisms that may explain this.

- The story moved with the migration of peoples and their descendants.

- The story diffused and was exchanged between distinct peoples.

- The story is universal because it expresses something about a fundamental human condition.

There is evidence for both the first two possibilities. In some cases, similarity of stories between cultures follows the degree of genetic relatedness. In other cases, geographical proximity better explains the distribution of the story. The third possibility makes a strong prediction that Is not borne out in the data. If a story is universal, it must be universal: in other words, it should appear everywhere in all cultures. Even in such a widely distributed mytheme as the Rainbow Serpent, the map shows significant gaps: in north Africa, north Asia and is rare in north America.

Some researchers are sceptical about the underlying narrative inferences, arguing this is subjective. When we say stories are similar, how similar are they really? Are we forcing the evidence into preconceived boxes? Is the Greek myth of Callisto really the same Cosmic Hunt story as in the Iroquois tale of the three hunters pursuing a bear?

The Cosmic Hunt (from D’Huy)

A woman breaks a taboo; A man is hunting an ungulate; the hunt takes place in the sky or ends there; a divine person stops the hunter and transforms the animal into a constellation (sometimes, the one we know as Ursa Major),

Perhaps, yes. In both stories (and in many other variants) a quarry is turned into a constellation. On the other hand, perhaps, no, The strong claim that widely distributed stories (such as the Rainbow Serpent or the Cosmic Hunt) must link back to the time before modern humans emerged from Africa needs strong evidence. It would be seductive to believe we can reconstruct tales told around Palaeolithic fires, but diffusion may be a more plausible explanation than that stories can persist for 100,000 years[3].

A subsequent post will look at archaeological evidence for ancient stories

[1] Sara Graça da Silva and Jamshid J. Tehrani (2016) Comparative phylogenetic analyses uncover the ancient roots of Indo-European folktales, R. Soc. Open Sci.3150645 http://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150645

[2] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/scientists-trace-society-rsquo-s-myths-to-primordial-origins/

[3] Andrew Cutler (2023) Contra d’Huy on Snake Myths https://www.vectorsofmind.com/p/contra-dhuy-on-snake-myths; Bortolini et al (2017) Inferring patterns of folktale diffusion using genomic data. PNAS 114 (34) 9140-9145 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1614395114