Culture shapes (and constrains) how we understand the world. For example, in a hierarchical society, the perception of groups of things tends to be ranked. Language both expresses and shapes culture, as well as, in turn, changing as culture changes.

A Portuguese friend once remarked, as we shared a bottle of rum on a beach, that the trouble with English speakers is that they only know one way of being. Portuguese, of course, has two verbs “to be” — one used for permanent states (like “I am Portuguese”) and the other for temporary states (like “I am ill”).

Grammar alters our understanding in quite profound ways. Many languages have gendered nouns. The word for bridge in Spanish, for example, is masculine, while its German equivalent is feminine. This does not happen in English. There are also languages that dispense with the need for gendered pronouns (“he” and “she”). Proto-Indo-European, the root language of whole families of present-day tongues, distinguished in pronouns only between living and non-living.

More profoundly, some languages (Hopi, for instance) lack a future tense, complicating conjectures and plans for the time to come. The same was true of Anglo-Saxon and of Proto-Indo-European—they had present and past tenses, but no future. Such a grammar probably reflects a society in which the future was likely to be pretty much like the present.

In turn, while many of us today conceive time as an arrow, a lack of a future tense may well favour a cyclic notion of time. This is, of course, more than a matter of the simple existence of tenses. Other factors are at play too. In European-speaking cultures, we tend to picture time as horizontal, with the future ahead of us and the past behind. Not so in Mandarin, where earlier events are “up” and later events “down”.

As an aside, not all features of our sense of time are coded in language. Research shows that different cultures, even within the same language group, may have different senses of how important the past is compared with the future. Compare the future orientation of US respondents to those from the UK in this diagram, which comes from the book Riding the Waves of Culture by Fons Trompenaars and Charles Hamden-Turner.

What of some other basic features of grammar? There can be little in English more fundamental to an elementary education than learning to distinguish between subject and object. A subject is a noun describing the originator of an action. In the sentence “The man ate the dog”, the subject is “the man”. Likewise, an object is a noun upon which the action happens, in this case “the dog”. The separation of the universe into active subjects and acted-upon objects is a philosophical fundamental. From it, arguably, a whole worldview flows. We cannot say which came first, the grammar or the worldview, but they buttress each other to create an understanding of how the world works that appears to us unquestioned commonsense. In reality, of course, it is a cultural convention, albeit one with deep roots in the dominion over nature and over other people.

Likewise, it is commonsense for us to distinguish between the actor (the noun) and the action (the verb). But not all languages do this. For example, though there is controversy about the claim, it is said that the Salishan language family of the Pacific Northwest of North America does not have this actor/ action distinction.

So how does all this affect the stories we tell?

1. The separation of subject and object

The grammar here entices us to see the world as divided into subjects who act and objects which are acted upon. This convention provides the soil from which spring knights errant and tales of derring do—in short, the heroic protagonist.

Alternatively, we might tell stories that do not depend on identification with a protagonist, but perhaps those that focus on the situation and on the society. Arguably, some Asian story forms are of this nature. Here, for example, is a summary of the Japanese story The Gratitude of the Crane.

Once upon a time, an old man finds an injured crane in the woods and nurses it back to health. One day, a beautiful girl comes to his doorstep, saying she is lost. The old man takes her in, and the girl tells him not to open the door at any noises. The old man opens the door anyway when he hears strange noises and finds a crane using its feathers to weave an extraordinary piece of cloth. Having been seen, the crane flies away.

Western stories are rational, and depend on clear ideas of cause and effect, and distinctions between what is objective and what is subjective. But this is not necessarily true of the literature of other cultures. Ming Dong Gu, in his Chinese Theories of Fiction, argues that Chinese fiction is fantastical rather than realistic. Things arise out of nothing; the Chinese story is full of interconnections and transformations between the world of humans and the world of nature.

2. The separation of actor (noun) and action (verb)

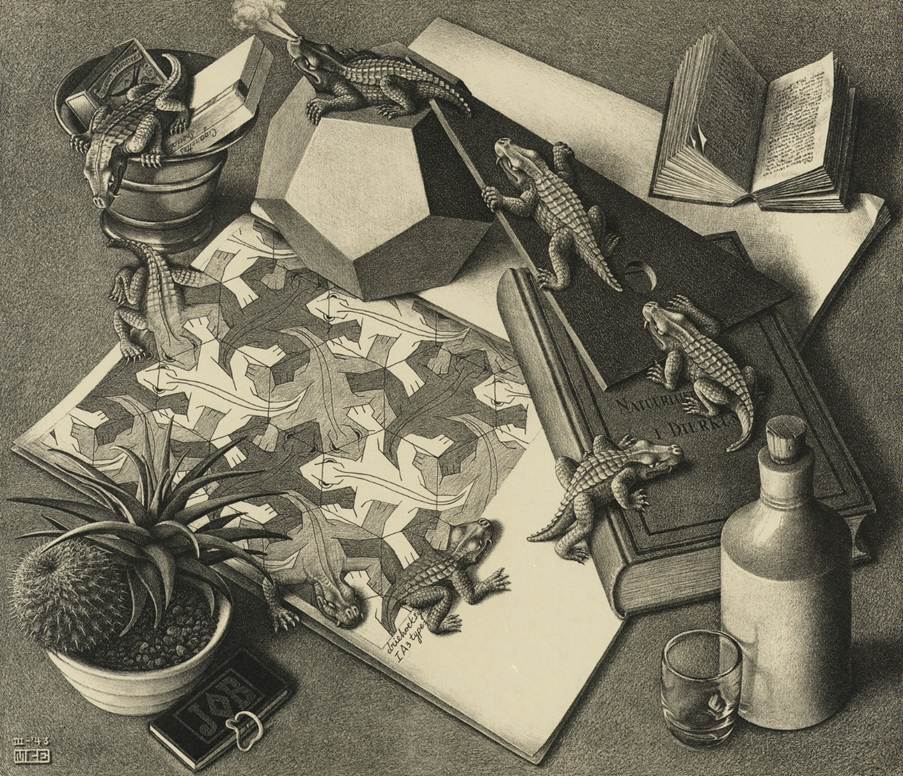

The consequences here are more subtle. They nudge us towards perceiving entities and events rather than underlying processes. We say, “the cat sat on the mat”. But from a different perspective, we might view the entities (cat and mat) as processes, extended in time and subject to change: catting and matting. We might also see the event (sat) as a process (sitting). If we adopted this perspective, what stories might arise? They might be stories with a stronger sense of transformation and of great time spans. Here, for example, is an experimental piece, The Quantum Cat, I wrote, exploring this possibility.

The catting satting on the matting, ideaings passing through their heading: ideaings of dinnering and of hunting. A womaning was arriving. They were holding out feeding to the catting.

The wave function collapsed. And the cat sat on the mat.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that language determines consciousness, but it does play a part in shaping how we imagine the world.