How good is AI nowadays at writing stories?

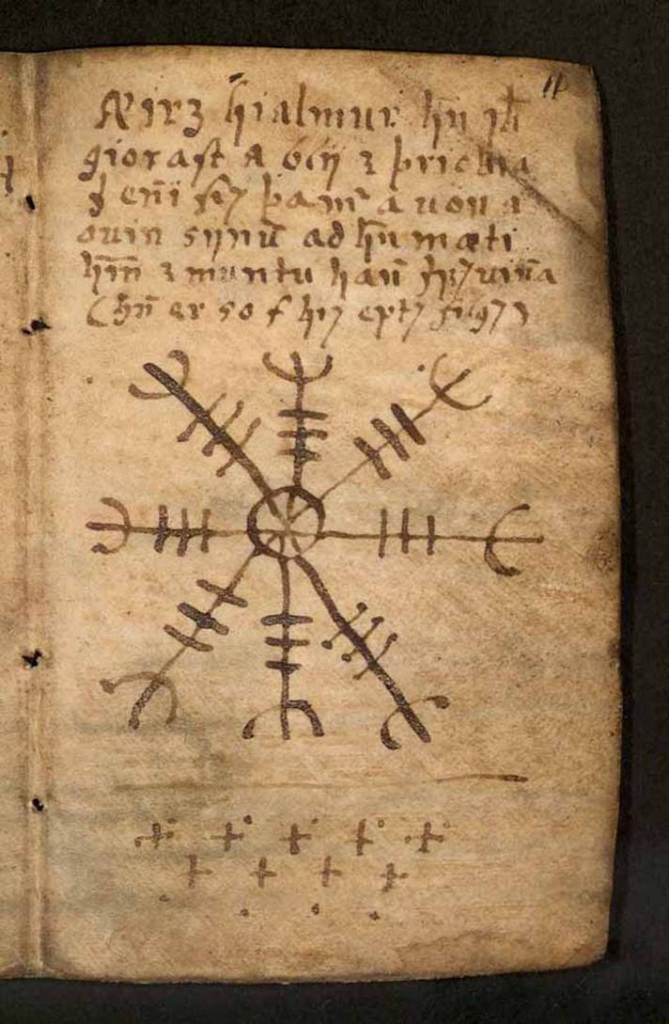

I decided to put this to the test, using ChatGPT. I took the prompt from this week’s Friday Fictioneers group, which is this photograph,

PHOTO PROMPT © Lori Wilson

Friday Fictioneers is a weekly challenge to write a 100 word story based on a photo prompt.

My first prompt and resulting story wre the following:

Write me a 100 word story based on a small diner called Shelly’s Route 66 cafe. which is covered in red, white, and blue bunting with a statue of a chef and two trestle table outside

1.

Shelly’s Route 66 Cafe squatted beside the highway like it had grown there, wrapped in red, white, and blue bunting that fluttered in the desert wind. A plaster chef stood guard by the door, mustache proud, spoon raised in eternal welcome. Two trestle tables waited outside, sun-bleached and carved with initials from travelers chasing somewhere better.

Every morning, Shelly brewed coffee strong enough to wake the ghosts of old road trips. Truckers, dreamers, and runaways found their reflections in her chrome counter. By night, the neon hummed softly, and the little diner held the road’s secrets close.

Microsoft’s Copilot delivered a similar story in response to the prompt. The stories were about the café rather than people so I altered the prompt to foreground the people and got the following output:

Write me a 100 word story about Shelly’s suitor, set in a small diner called Shelly’s Route 66 cafe. which is covered in red, white, and blue bunting with a statue of a chef and two trestle table outside

2.

Shelly’s suitor arrived at dawn, parking his dusty pickup outside Shelly’s Route 66 Cafe, where red, white, and blue bunting fluttered like nervous flags. He paused beside the chipped statue of a chef guarding the door, smoothing his tie in its metal reflection. Two trestle tables waited outside, still damp with morning dew, as if expecting witnesses. Inside, coffee hissed and the jukebox hummed softly. He had rehearsed his speech all night between miles of highway. When Shelly looked up from the counter and smiled, he forgot every word—except her name, which felt like home.

It still felt a bit mechanical so I tried a third prompt:

Write me a 100 word story in the style of Jack Kerouac about Shelly’s suitor, set in a small diner called Shelly’s Route 66 cafe. which is covered in red, white, and blue bunting with a statue of a chef and two trestle table outside

3

He blew in like a freight train ghost with dust in his cuffs and a grin stitched from the long American highway, and Shelly watched him from behind the counter at Shelly’s Route 66 Cafe, where the red, white, and blue bunting fluttered like patriotic heartbeats against the windows. The statue of the chef out front kept its porcelain smile while two trestle tables baked in the noon sun. He talked about Tulsa mornings and desert stars, coffee shaking in his hand, calling her “baby” like a prayer, and she felt the road humming in her bones, wild and wanting.

Some observations on these stories:

- The quality of the story, to some extent, depends on the quality of the prompt. The AI emphasises the things that seem important from the way the prompt is crafted. In the first example, the story opens with the diner, while in the second it opens with the suitor. The third changes the voice to something less mechanical.

- The algorithm throws in the odd metaphor and descriptive detail. These may sound writerly but they tend to be a bit off. Freight trains, for example, do not blow in. And I have no clue what trestle tables expecting witnesses might mean.

- The structuring of the ending is where the AI really goes to work to create an upbeat vibe. In the first story, the little diner holds the road’s secrets close. In the second, Shelly’s name feels like home to the suitor. In the third, more interestingly, the interiority shifts to Shelly, who feels the road wild and wanting. It would have been possible, of course, to prompt for a sad ending.

For comparison, my own story for this prompt was:

The diner’s unremarkable. Could be anywhere, and almost anywhen. But Shelly, she is remarkable—tough, with a head of hair like springs and a tongue like a buzz-saw. I’ve had a thing for Shelly for near on thirty years.

“You can get anything you want in Alice’s Restaurant, exceptin’ Alice,” as the song goes. That’s Shelly’s. I turned up once with a mariachi band and a convertible full of red roses, like that Richard Gere movie. Woman only sniffed and muttered, “damn fool boy.”

Suppose you might call me a stalker, except the relentless pursuit really tickles Shelly. One day she’ll succumb.