Some simple tips can make your prose more vivid. This week it was my turn to lead an exercise in my writing group on the elements of description. This what I said:

We use descriptive writing to describe a person, place or thing so that a picture is formed in the reader’s mind. This connects to the difference between showing and telling. When a writer tells something s/he merely communicates what happens. When s/he shows, the reader is drawn into the scene.

There are four main things to remember for good descriptive writing.

Use vivid sensory details

- Use precise language. Avoid general nouns, adjectives and verbs. Use specific words and strong verbs to build the picture. For example, “he scrambled up the scree” is more powerful than “he ran up the hill”.

- Make use of images, similes and metaphors.

- Use all the five senses – sight, touch, smell, hearing, taste. Practice just observing quietly.

Less may be more. When describing a landscape, you’re trying to portray it comprehensively and precisely but not necessarily exhaustively.

- Think about what’s important. A telling phrase to encapsulate a scene or a character can be better than a paragraph. For example. For example, this description of a distressed soldier in a story I wrote: “As he spoke, he drank, like he was firing and reloading a rifle, technically, methodically.”

- Hemingway, famous for sparse descriptions of his characters, held that “action is character” and that “dialogue is also action and a projection of character”.

It’s not just exteriors. Link to feelings too.

- You’re not simply describing a landscape within which your characters move. Allow the physical and emotional worlds interact. Description is more powerful when you show the gears turning inside those psyches.

- Leslie Jamison advises “If you’re describing a chair, let your mind play with all the different things that chair could mean to various characters. Whose feelings were hurt in that chair? Who was betrayed in that chair? Who broke into his estranged father’s property to chop down the tree whose wood was used to build that chair?”

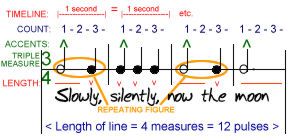

It’s not only about the words. Think, like a poet, about rhythm. The sound and rhythm of the words can capture a description.

- For example, look at how the rhythm captures the soul of these two ships in John Masefield’s poem, Cargoes:

“Quinquireme of Nineveh from distant Ophir,

Rowing home to haven in sunny Palestine.”

And

“Dirty British coaster with a salt-caked smoke stack,

Butting through the Channel in the mad March days.”

Exercise

This exercise is a technique for observing quietly.

Sit quietly for 5 minutes. Try to clear your mind. Don’t judge, just observe. DON’T WRITE DURING THE OBSERVATION PERIOD. Then write down, for each of the senses, the things you saw, heard, felt, smelled and tasted.

When you’ve done that, take another five minutes and try to come up with some great words or short phrases than would summon up a few of those things.