It only recently occurred to me that the concept of point of view in literature is a metaphor, borrowed from painting. I am still struggling to see if anything profound flows from this realisation. Bear with me, please.

When we write from the point of view of a particular character, we see events from a particular place in the story world. Point of view in fiction is like perspective in painting. Perspective creates the illusion of an image as seen by the eye if viewed from one particular spot.

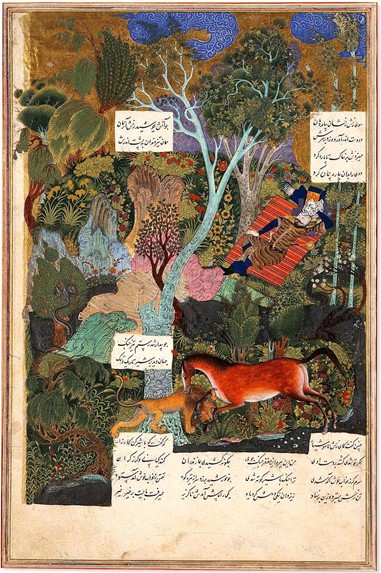

Perspective is intended to create an illusion of realism. We are so used to seeing it in painting that we don’t notice it as a technique and see it as representational. But of course there were and are other conventions in the history of art. In the Persian tradition of miniature illustration, recession into the distance is indicated not by size but by being placed higher up the picture, horses are generally depicted from the side and the scene is often viewed from above. Viewing from above is akin to the world as seen by God.

Can there be fiction without perspective?

If there can painting without perspective can there also be a fiction without perspective, without point of view? It’s a seductive but impossible idea. All fiction has an inescapable point of view. A story has to be told by someone. But stories can be told in different ways and this has echoes of different conventions of representation in painting.

The world as seen and the world as it is

These days, a first-person or close-third-person narration is common. It makes our experience of the narrator more intimate, but it also adds perspective to the telling. There are objects that are hidden from the view of the narrator, and the constant possibility of distortion – the narrator misunderstanding the meaning of events.

By contrast, a century and half ago, the omniscient narrator was common. Like the period before perspective in art, the narrator could dip in and out of the heads of different characters, revealing their thoughts and their intentions. Important events could be foregrounded. This was like the technique of drawing a scene not as viewed by the painter but the real scene as viewed by God.

The dimension of time

I sense there may be something more interesting in comparing perspective and point of view, but I can’t discover what it is. It may have to do with the way in which painting and writing are different. While a painting is fixed, a story always has some sort of motion in time. Unlike artists, writers have enormous freedom to explore and play with time. Few stories are told linearly from beginning to end. Rather there are flashbacks, fore-shadowing, cliff-hangers, misdirection, and ellipses. There may be stories within stories. And, in the technique of metalepsis, logical boundaries between story levels can be transgressed, as when the narrator intrudes into a world being narrated. The timeline can become extensively fractured in some tales. This too is like the fracturing of perspective in modern art.

Help

Can you do anything to take these insights further?