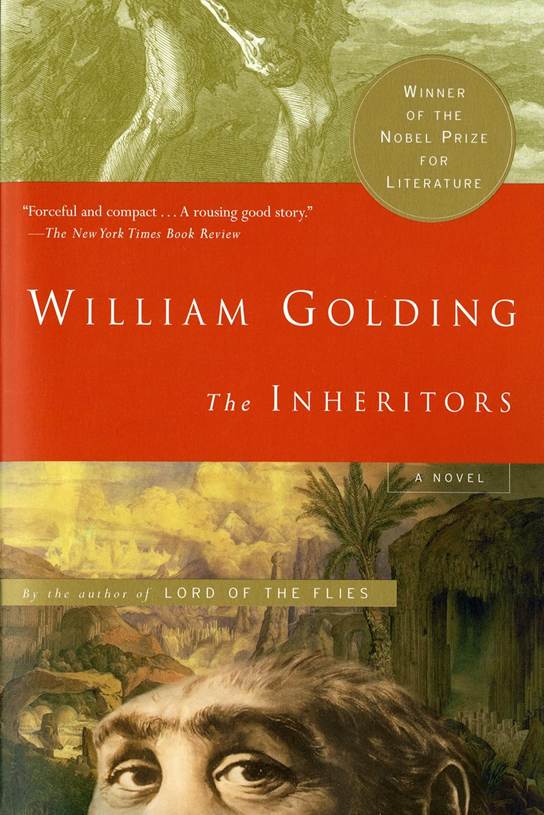

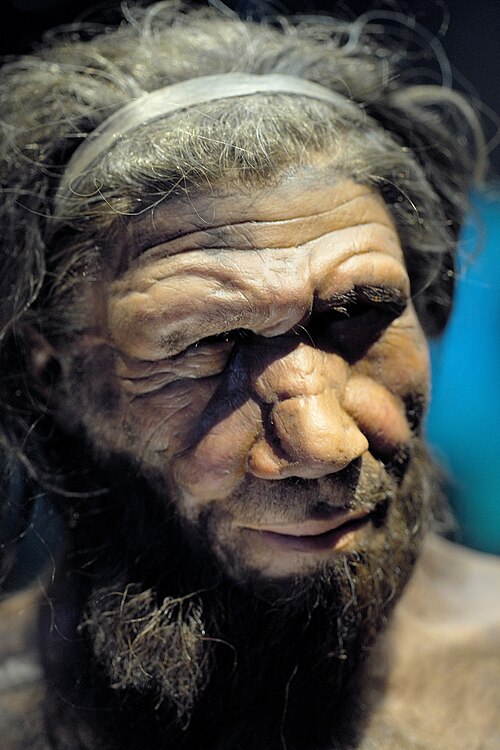

Golding thought The Inheritors was his finest novel. It tells the story of a band of people about to be displaced by stronger incomers. The twist is the people are Neanderthals, and the incomers are modern humans,

Like all of Golding’s work, there is a moral subtext. Lok, Fa and the other Neanderthals in this tale of The Fall are innocent and without sin, while the Homo Sapiens are licentious, drunk, and violent.

What makes this book extraordinary is the language Golding uses to craft Lok’s inner world. His Neanderthals inhabit a rich sensory world heavily imbued with life force, capable of almost telepathically sharing images, and without much in the way of concepts. We are immersed in a strange and charmed world.

How does Golding achieve this effect?

The grammar of an alien mind

When we are in Lok’s head, sentences are short and staccato. The book opens “Lok was running as fast as he could.” The Neanderthals’ speech is simple and declarative, dealing with the immediate and the concrete.

Of course, a novel composed entirely of such clipped sentences would be like a child’s reading primer. So Golding complements this with highly sensory and lyrical description, especially of colour.

By contrast, the Homo sapiens use longer sentences with subordinate clauses. This is a speech capable of conveying abstract thought, of understanding the relations between things. Consider the metaphoric quality of :

“His teeth were wolf’s teeth and his eyes like blind stones.”

Transitive and intransitive verbs

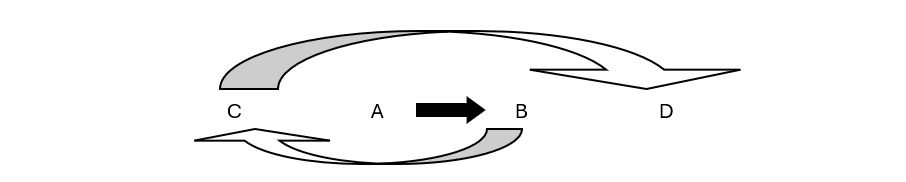

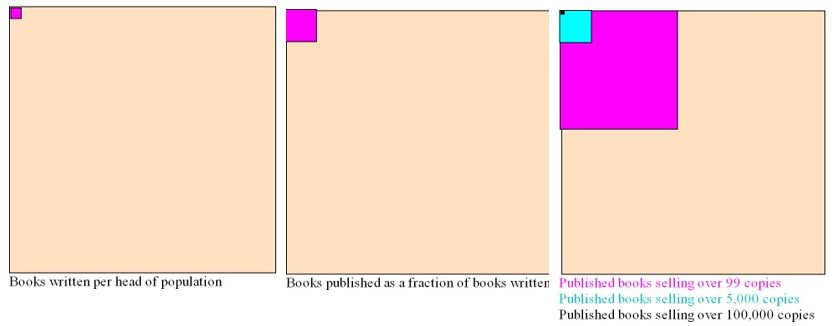

The passages dealing with Lok and the Neanderthals rarely (18.47%) uses transitive verbs, while in the passages from the perspective of modern humans such verbs are more common (40%)[1] Transitive verbs are those which require an object to complete them (for example, “Vivani was doing her hair”) whereas intransitive verbs are complete actions in themselves (for example, “Lok ran”). Clearly, we use transitive verbs to express more complex ideas and understand our being in the world.

Fa, the cleverest of the Neanderthals, almost imagines the idea of container for carrying water from the river. But the mental effort proves too much for her and the picture vanishes. Lok is often unable to piece together complex cause and effect. This is clearest in the passage where Lok first encounters a man from the new species:

The man turned sideways in the bushes and looked at Lok along his shoulder. A stick rose upright and there was a lump of bone in the middle. Lok peered at the stick and the lump of bone and the small eyes in the bone things over the face. Suddenly Lok understood that the man was holding the stick out to him but neither he nor Lok could reach across the river. He would have laughed if it were not for the echo of the screaming in his head. The stick began to grow shorter at both ends. Then it shot out to full length again. The dead tree by Lok’s ear acquired a voice.

Clop!

His ears twitched and he turned to the tree. By his face there had grown a twig: a twig that smelt of other, and of goose, and of the bitter berries that Lok’s stomach told him he must not eat. This twig had a white bone at the end. There were hooks in the bone and sticky brown stuff hung in the crooks. His nose now examined this stuff and did not like it. He smelled along the shaft of the twig. The leaves on the twig were red feathers and reminded him of goose. He was lost in a generalised astonishment and excitement.

Lok is unable to work out that the man has shot an arrow at him.[2]

Identity

The uncanny sense of being in an alien mind isn’t just about sentence structure. Lok’s sense of identity is also different from ours. Parts of his body lead an autonomous life:

Lok’s ear spoke to Lok.

“?”

But Lok was asleep.

Or:

Lok’s feet were clever.

Everything has a life

Everything in their world is alive and participates in a common animation. The log, for example, has agency and has “gone away”, as if of its own volition, and the sun “hid again”.

Lok finds it difficult to stay focused on a task for long, being easily distracted by needs for food and sex. The others say “Lok has many words but few pictures.”

When the group discuss something they share mental images. If they don’t get it, they say “I do not see this picture.” They can even merge their consciousnesses to a shared picture in a kind of hive mind.

When things become confusing for Lok, particularly when the new people attack, he defaults to a genial optimism. He is unable to conceive that they have killed his comrades and abducted the two young ones. He looks forward to the girl, Liku, coming back when the new ones return her. It is Fa who works out that they are under mortal threat.

Homo neanderthalis and Homo sapiens

Unlike the modern humans, these people live gently on the earth, never killing to eat, subsisting on a diet of plants and roots, and meat only when they can scavenge from a predator’s kill.

By contrast, we see the Homo sapiens through Lok’s eyes as incomprehensible creatures who inspire wonder and fear. Their actions are rapacious and chaotic, while their bird-chirp language seems full of admonishment, sly manipulation, and domination.

The outcome

We already know that Lok and his friends will not survive this encounter, because they are gone, and only we are left. Golding is questioning whether that has been a good thing, whether we are a good thing, though he does not suggest we had a choice. For him, we belong on the upsweep of the evolutionary trajectory, represented by the river that runs like time through the novel’s landscape. But perhaps he mourns the fall of that innocence.

[1]Khalid El Khouch (2024) https://www.researchgate.net/publication/382456923_Transitivity_and_Stylistic_Analysis_aJourney_into_the_Language_of_William_Golding’s_the_inheritors

[2] See Sam Browse (2018) From functional to cognitive grammar in stylistic analysis of Golding’s The Inheritors, Journal of Literary Semantics, 47 (2), 121-146 https://shura.shu.ac.uk/23149/