I have started work on a new novel. set 9,000 years in the past in the ancient city of Çatalhöyük (on the Konya plain of what is now central Turkey).

This is a challenge. How did these people think? What was important to them? Writing had not yet been invented, so there are no texts to tell us what stories they told, what language they spoke, or what they called themselves. All of this has to be pieced together from the material remains of their impressive 2,000 year history. We know equality must have been very important to them. We can say this because, with minor differences, all the houses were pretty much the same.

Artist’s impression of Çatalhöyük

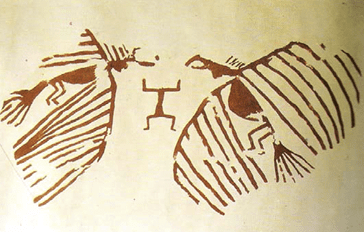

There were no temples, no palaces, and hence, no priestly class or kings. There was no indication of warfare. Their bones show that everyone was pretty well fed, with no nutritional differences between men and women. By this time, they had domesticated plants, goats and sheep. They could have domesticated cattle too, but chose not to because the hunt of the wild giant bulls, the aurochs, and ritual feasting was fundamental to their way of life. We know this because of the feasting remains and because they celebrated the hunt in extraordinary murals.

This article examines a selection of these murals, those found in house F.V.1 which dates from around 6,500 B.C. It was decorated on all four walls with the painting applied to a single layer of plaster. Why have I chosen to analyse these paintings in detail? Because there are clues here to what they believed, and from those and other clues I can try to rebuild a version of what their lives may have been like. I should stress, I am an author, not an archaeologist. It’s my job to make stuff up, but I want what I make up to be wholly consistent with what’s known from the archaeology.

In a journey round all four walls of the house starting from the south, these are the murals. A detailed description of the paintings and their location can be found in a paper by Grant Cox[1].

Painting 1. The Stag. Southwest corner

The painting shows 16 humans with a stag. There are no weapons, so this seems to indicate a scene of playing or baiting (one of the figures tugs on the reluctant animal’s tongue, one on its tail, one its antlers and one its hoof). The scene may be symbolic. Several of the figures are incomplete with missing and disarticulated body parts, including perhaps two missing their heads. The latter may suggest ritual or mythological significance. Alternatively, this may simply be the result of fading or damage to the painting

Several of the humans are rendered in some detail, showing noses, chins, hair and beards. One of the figures, rendered in pink, is unusual in not being a silhouette, the only such figure in all the murals. It is possible he is leaping on the stag’s back (though it is just as plausible to suggest he is behind the animal). Two of the human figures at the bottom of the picture are smaller (children?) and one is a woman (bottom right), Near the woman is what may be a dog.

There are indications of differences between the men. One has pink skin. Some wear leopard skin kilts and others what appears to be of a different animal (goat?)

| Pink skin colour | Red skin colour | Total | |

| Men | 1 | 12 | 13 |

| Women | 1 | 1 | |

| Children | 2 | 2 | |

| Disarticulated | 4 | ||

| Weapons | 0 | 0 | |

| Leopard kilt | 1 | 5 | |

| Other kilt | 4 | ||

| No kilt | 5 |

Painting 2. Several animals. Northwest wall.

After a separation by a plaster pillar, this painting appears above a long frieze of what appears to be a line of asses. Several animals are shown and 17 humans. This time, six of the people are armed. The top of the painting is dominated by two animals, one of them headless. Melaart interpreted them both as deer, the smaller one to the right being a different species (perhaps a fallow deer). However, the larger headless animal is rendered unusually for a deer and may be a bull or a cow. Again, headlessness may have a symbolic ritual meaning. Two of the humans are also headless, as is a small animal at the bottom right. Two of the humans are trying to net the boar. One of the men may be trying to balance on the back of the fallow deer and two on one of the asses (though it is equally possible they are simply depicted as being behind the animals).

Again, there is one woman on the bottom right and there are differences between the humans, with skin colours of black, red, and pink. None of them is wearing anything that can be clearly identified as a leopard skin kilt.

| Pink skin colour | Red skin colour | Black skin colour | TOTAL | |

| Men | 5 | 7 | 2 | 14 |

| Women (no kilt) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Children (no kilt) | 2? | 2? | ||

| Disarticulated | 1 | 1 | ||

| Weapon (bow) | 1 | |||

| Weapon (boomerang) | 2 | 1 | ||

| Weapon (other) | ||||

| Net | 1 | 1 | ||

| Leopard kilt | ||||

| Other kilt | 2 | 1 | ||

| No kilt |

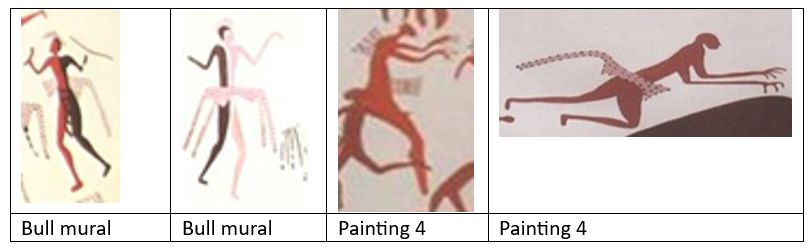

Painting 3. The Bull. North wall

This mural is dominated by the giant bull which dwarfs the people. Several of the people are armed. The skin colour is not easy to distinguish here as between red and pink. Some of the people have a lighter tinge, but not as light as pink and have been interpreted as red. Two of the figures are unique in being half tone (one half red and half black, the other half pink and half black). Both these figures also have leopard skin kilts, weapons and headdresses, indicating they may be high prestige. Again, there is one woman in the picture, apparently pregnant (just below the bull) and one child, seemingly tethered to an adult (just behind the bull).

| Red skin colour | Black skin colour | Half tone | TOTAL | |

| Men | 23 | 4 | 2 (pink & black, red and black) | 29 |

| Women (Pregnant) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Children | 1 | 1 | ||

| Disarticulated | 1 | |||

| Weapon (bow) | 4 (2 kilt, 2 no kilt) | |||

| Weapon (boomerang) | 2 | 1 | ||

| Weapon (other) | 4 | 2 | 1 | |

| Net | ||||

| Leopard Headdress | 2 | 2 | ||

| Leopard kilt | 14 | 4 | 2 | |

| Other kilt (red) | 10 | 1 | ||

| Other kilt (black) | 4 | |||

| No kilt | 11 |

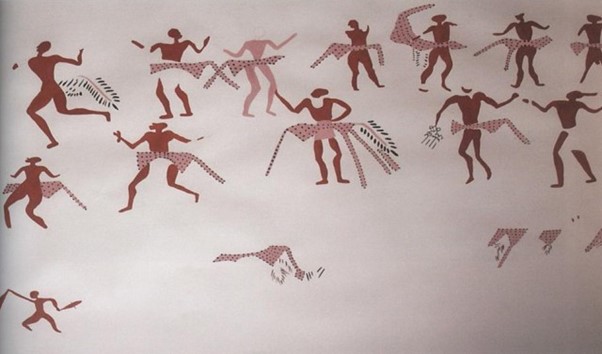

Painting 4. Northeast corner continuing onto the east wall

15 men are teasing a stag and a bear, pulling on tongue and tail. The empty leopard skins suggest there might have been more people, lost through the poor condition of this part of the wall. Though three of the men are armed, this does not seem to be a hunting scene. The two figures below the stag’s jaw appear to be in synchrony. Is the pale on a cosmic mirror of the red one? The figure just below the stag’s forefeet and trying to pull the bear’s tail appears to be a human-animal hybrid, with spines on its back and extended claws.

There are no women or obvious children in this scene, though it’s possible the bending figure just below the bear’s rump is a child.

| Pink skin colour | Red skin colour | Black skin colour | TOTAL | |

| Men | 2 | 13 | 15 | |

| Women | ||||

| Children | ||||

| Disarticulated | 2 | |||

| Weapons (bow) | 1 | |||

| Weapons (boomerang) | 2 | |||

| Leopard kilt | 1 | 4 | ||

| Other kilt | ||||

| No kilt | 10 |

Continuation of painting 4 on north side of east wall

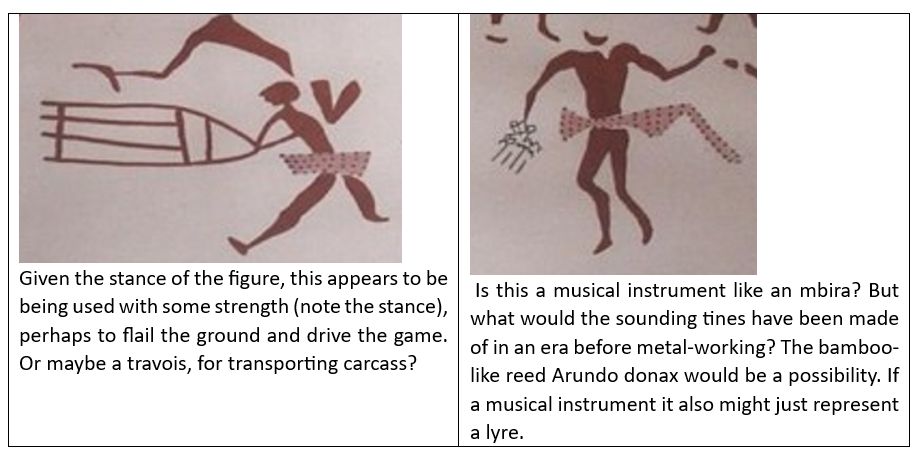

The painting continues onto the east wall, showing a boar and bear apparently being baited. Again, weapons are present, as well as a mysterious harp or flail like object. Only one type of person is represented (with red skin). The figures just below the boar’s snout and the one apparently on its back may be wearing feathers.

Of particular interest is the figure leaping at the back of the bear, another seeming human/animal hybrid with extended claws.

| Pink skin colour | Red skin colour | Black skin colour | TOTAL | |

| Men | 12 | 12 | ||

| Women (no kilt) | ||||

| Children (no kilt) | ||||

| Disarticulated | 2 | |||

| Weapon (bow) | 0 | |||

| Weapon (boomerang) | 2 | |||

| Weapon (other) | 2? | |||

| Net | 0 | |||

| Leopard kilt | 3 | |||

| Other kilt | 0 | |||

| No kilt | 9 |

Painting 4 continued (southern part of east wall)

This panel (though it is a continuation of the previous one) is the only one that contains no animals, though the majority (perhaps all if the paint has fade) of the 13 men wear leopard skin kilts as if they were about to face dangerous game. Perhaps this represents the aftermath of a hunt, or a ceremony preceding a hunt. The figures appear to be circled (dancing?) around a magnificently dressed central figure, whose leopard skin seems to be feathered (as is that of the figure on the top left). Again, there may once have been more figures who have faded leaving only their leopard skins at the bottom of the picture. Only one person holds what may be a weapon (a boomerang) and one, on the right of the central figure holds a mysterious object with tines.

| Pink skin colour | Red skin colour | Black skin colour | TOTAL | |

| Men | 1 | 12 | 13 | |

| Women (no kilt) | ||||

| Children (no kilt) | ||||

| Disarticulated | 1 | |||

| Weapon (bow) | ||||

| Weapon (boomerang) | 1 | |||

| Weapon (other) | 1 (tined) | |||

| Net | ||||

| Leopard kilt | 1 | 9 | ||

| Other kilt | 0 | |||

| No kilt | 3 |

Painting 5 (South side of east wall)

The image begins after the bench on the east wall and continues to the ladder. Preservation was particularly poor here. A large pink feline creature (possibly a leopard although there are no spots) is surrounded by at least 9 people (more may have been lost to fading), none of whom are armed, though all are wearing leopard skins. The skins this time appear to be feathered. All are men and all are coloured red. The men appear to be holding hands and may be dancing One of the men, with a fine double kilt, is also wearing a leopard skin hat.

| Pink skin colour | Red skin colour | Black skin colour | TOTAL | |

| Men | 9 | 9 | ||

| Women (no kilt) | ||||

| Children (no kilt) | ||||

| Disarticulated | ? (damage) | |||

| Weapon (bow) | 0 | |||

| Weapon (boomerang) | 0 | |||

| Weapon (other) | 0 | |||

| Net | 0 | |||

| Leopard kilt | 9 | |||

| Other kilt | 0 | |||

| No kilt | 0 |

South wall

The murals conclude with an incomplete set of human and animal images on the south wall.

Interpretation

- The collection of images are not of hunting alone. Indeed, only the bull mural seems to depict anything that could be considered a hunting scene. But the other scenes may be part of a wider symbolic complex: the prowess-teasing-hunting-feasting complex. The bull mural is the only one in which almost half the participants are carrying weapons (14 weapons among the 31 participants). By contrast, the proportion of weapons in the two stag teasing scenes (painting 1 and painting 4) are zero and 3-in-15 respectively. Teasing (a display of prowess) was probably an important part of the symbolic complex. Even in the bull hunt scene, one of the participants seems to be performing an acrobatic tumble on the bull’s back. Other images too may indicate participants vaulting the animals (paintings 2 and 4, possibly painting 1).

- These scenes depict predominantly, if not exclusively, adult male activities. The individual women present in several of the scenes may have been symbolic, particularly because one seems heavily pregnant. It is probable that boys would have been part of the hunt when they came of age.

- Though the bull hunt scene shows 31 individual (which is probably the minimum number that would have been required to hunt the wild aurochs) these scenes should probably not be read as a realistic depiction of actual activities and may be highly symbolic in nature. Reasons for believing this include

- The probably symbolic nature of the female presence in three of the panels

- The scale, with the animals represented larger than life

- The presence of hybrid figures who may be symbolic or mythological. The first two are status hybrids, while the second two seem to be animal-human hybrids. The projections from the back of the upright figure in painting 4 may be spines (maybe an iguana or a chameleon?) or feathers (feathers being more likely since it appears predatory: maybe an eagle?). The leaping figure in painting 4 may be a leopard-human hybrid.

- The disarticulated bodies (particularly the headless ones) may be indication of a spiritual state. At least some, however, may just easily be the result of damage and fading. Headlessness, however, was an important feature of ritual life. Skulls were retrieved from some corpses and subject to manipulation. On closure of a house, the heads and limb extremities were struck off the splayed figure reliefs.

Headless bodies also occur in the vulture paintings found in level VI

4. There are various differentiators between people in the images

- The colour coding of the figures is intriguing. Did red, pink and black indicate different social groupings (perhaps those clustered around a “history house”) or, alternatively, different occupations or, yet again, different ages? Red figures predominate in all the scenes, reflecting perhaps the lineage that lived in this house. It is possible that pink wasn’t a real category but the result of red paint fading. The half-tone figures in the bull mural may represent some status (again, perhaps mythological) that bridged the two groups. The fact that there are no three-tone figures, may add weight to the suggestion that the pink is an artefact of ageing, because more than two house groups would have been required for the hunt. It seems most plausible that the colour coding represents neigbourhoods.

- Do the colours represent house groups? The minimum number of hunters to successfully bring down a bull was probably around 30. Assuming an average of two adult males per household, this figure would require cooperation between at least 15 houses. With five or six houses grouped together around a “history house”, the minimum hunting number would have required cooperation of at least three such house groups, and probably more participated. If the colour-coding represented such house groups, at least three colours would be required, but probably more. Yellow was a colour available to the painters but was not used. It seems likely, therefore, that the colour coding did not represent house groups. It could however have represented the neighbourhood level. Houses were clustered into neighbourhoods or quarters of around 30 houses[2]. If a hunt was organized by a neighbourhood, with some members of other neighbourhoods participating, the colour coding would find a ready explanation. The half-tone figures would also be explained as individuals whose lineage or affiliation spanned neighbourhoods.Do the colours represent occupation? The idea that the colour coding represented different occupations (for example herders, carvers, millers) also seems unlikely for two reasons: firstly, in this early and highly egalitarian society, it seems likely that most people performed most activities. Undoubtedly some may have specialized, being recognized as having an expertise in, say, stone working or painting, but they would undertaken other work too. The second argument is that these scenes appear symbolic, reflecting aspects of life that were spiritually important. There are no representations of the mundane activities that would have occupied the majority of people’s work time (farming, gathering, herding, stone-working etc.). Any distinctions between people in these paintings would have reflected spiritual not temporal differences. This argument would not apply, of course, to different roles within the hunt (such as drivers who moved the beasts towards the hunters who killed them, trackers, bearers).Do the colours represent spiritual status? Age would be the most obvious marker of such status. Children would have dependent status and youths (represented in black?) would have a candidate status relative to adult hunters (represented in red?). However, against this interpretation is the fact that apparent children are colour coded with what should be adult status (red). Also against this equation of colour with age grade or other spiritual status is the fact that some of the figures in black are wearing leopard skin kilts (which may have been a badge of status).

- Dress is a significant differentiator too: particularly whether or not a person wore a kilt, and, if so, whether it was leopard skin or some other skin. Leopard caps are also worn by some. The fact that leopard kilts predominate in the bull mural (worn by 18 of the 31 people, compared with 6 of the 16 in the stag teasing scene of painting one and with 5 of the 15 people in the teasing scene of painting four, suggests leopard skins had a particular status. When you went out to kill a bull, you needed the leopard’s protection. Interestingly some figures are dressed in kilts that appear to have been other animals (possibly goat), perhaps indicating they had no yet reached leopard rank. Interestingly, all those with the leopard in painting four (which is not a hunting scene but may represent a ritual) are wearing leopard skins. A final noteworthy feature about dress is the feathering worn on the skins by a few individuals in painting four (southeast wall) and painting five.

5. The meaning. The paintings represent much about the spiritual practices involved in the hunt, though interpretation is conjectural. Painting five shows a group of hunters invoking the spirit of the leopard to strengthen and protect them in the hunt. This would perhaps have marked the stage before they set off. The invocation was not simply symbolic. They did not simply dress as leopards in the skins of the animals, but they “became” leopards. Painting four shows the hunt in progress, with one hunter who has transformed into a leopard, leaping on the back of a bear. Other animal spirits too would come to the aid of the hunters. In the course of the hunt, much time was spent demonstrating bravery by teasing the wild animals, including vaulting over the animals, like the daring bull leaping perhaps shown in painting three. At the end of the hunt, there might have been further rituals. We know that feasting was the important ritual terminus, but it seems possible that the panel of painting 4 on the south-east wall may represent a dance of thanks. The seasoned hunters, dressed in leopard skins, are circulating round a magnificently dressed central figure, and one has what may be a musical instrument.

6. Mystery objects

7. What were these paintings for? They should not be thought of as “decoration” or “art” in the modern sense, because they would have been hard to view in the dim interior of buildings lit only from the entry hole in the roof. It is likely that they memorialized important events in the prowess-teasing-hunting-feasting cultural complex. It has been suggested that, in general, the act of making pictures may have been more important than the viewing of them. Wall paintings were normally quickly covered up by annual replastering of the walls, though this particular house had only a single layer of plaster. Given that unusual fact, it is possible that the pictures were used in celebrations and perhaps in initiation rituals within the group who used this house.

8. The aesthetic that flowered in levels VI and V (around 6.500 B.C.) was brief. Such paintings are not encountered again after level II (around 6,100 B.C.). Did aesthetic preferences change, or the culture as whole? Evidence is that the culture itself was changing, with more demands on labour time cutting into the time for collective activities like the bull hunt, together with a growing individualism. Aesthetic activities were now increasingly expressed in the more mobile pottery and seal stamps, perhaps as social bonds loosened. My novel is set at the time of this change.

[1] Grant Cox (2015) Çatalhöyük – The Shrine of the Hunters (F.V.I) https://artasmedia.com/2015/03/10/catalhoyuk-the-shrine-of-the-hunters-f-v-i/

[2] Bleda S. During (2005) Building Continuity in the Central Anatolian Neolithic: Exploring the Meaning of Buildings at Asıklı Höyük and Çatalhöyük Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 18.1 (2005) 3-29 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279697424_Building_continuity_in_the_Central_Anatolian_Neolithic_exploring_the_meaning_of_buildings_at_Asikli_and_catalhoyuk

I didn’t read the whole article, but you are doing some keen study on the area where your new book is set. Good to hear you’re writing a book about it. Can’t wait to read what you come up with in it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much, Jade

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome.

LikeLike

p.s. in the first image, the animal next to the woman looks like a doe maybe? or an auroch fawn? Maybe the men surrounding the auroch wrestle it to the ground and the guy with the spear does the killing?

LikeLike

Yes, could be a doe

LikeLike