Sunset Song by Lewis Grassic Gibbon is, in my view, one of the great books of the twentieth century. Re-reading it now, I am struck by how achingly beautiful and how angry it is, and by how cleverly it is constructed.

“She walked weeping then, stricken and frightened because of that knowledge that had come on her, she could never leave it, this life of toiling days and the needs of beasts and the smoke of wood fires and the air that stung your throat so acrid, Autumn and Spring, she was bound and held as though they had prisoned her here. And her fine bit plannings!–they’d been just the dreamings of a child over toys it lacked, toys that would never content it when it heard the smore of a storm or the cry of sheep on the moors or smelt the pringling smell of a new-ploughed park under the drive of a coulter.”

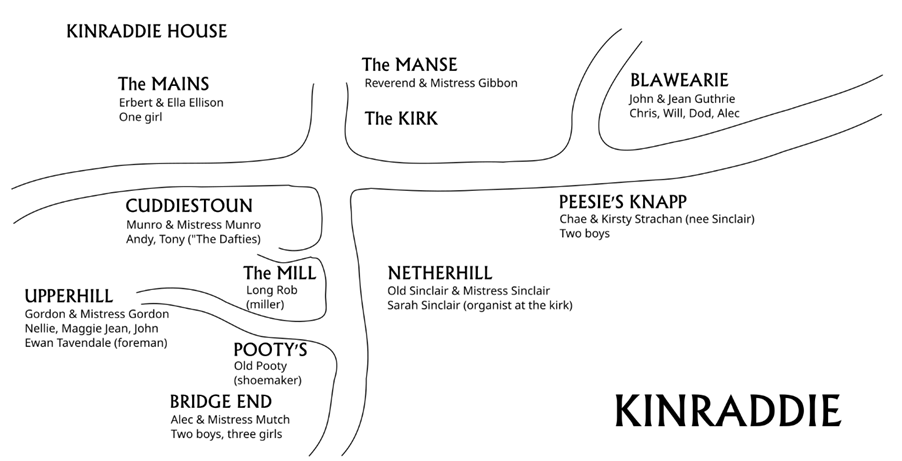

If it has any parallel in it picture of the bustling small life of the folk of Kinraddie, it can only be Dylan Thomas’ Under Milk Wood.

Themes

Above all, the theme is the land. The land which abides when all the folk who till it are dead and gone. Both the prelude and the epilude which bracket the book have the same title, “The Unfurrowed Field”, representing the unworked land. The book is a lyrical, brawling, angry and tormented paean to the dying age of the Scots peasant. And here too is a theme: of change and changelessness.

The protagonist, Chris Guthrie is herself the land (or perhaps all of Scotland). In Chapter 1, Ploughing, she is new ploughed for the immense changes that are coming. All the chapter titles represent the cycle of the growing season and the maturation of Chris. Chapter 2 is Drilling (in which her mother commits suicide and her abusive father is stricken with paralysis). Chapter 3, Seed Time, sees Chris’ father die and her inherit the croft. She marries Ewan. In Chapter Four, Harvest, Chris gives birth, Ewan leaves Chris after an unresolved argument to soldier in the First World War, where he is shot as a deserter. Many of the chapters open and close with Chris at the ancient standing stones, a symbol of deep time that brings Chris peace.

There is the theme of ambiguity. Chris is continually loving and hating things, afraid and intrigued. This replicates the author’s ambivalent feelings towards the birthplace he shunned.

And there is also the theme of social justice, a thrumming disdain for those who put on airs or who exploit others.

“Maybe there were some twenty to thirty holdings in all, the crofters dour folk of the old Pict stock, they had no history, common folk, and ill-reared their biggins clustered and chaved amid the long, sloping fields. The leases were one-year, two-year, you worked from the blink of the day you were breeked to the flicker of the night they shrouded you, and the dirt of gentry sat and ate up your rents but you were as good as they were.”

Humour

None of this makes it a dour book. It is full of humanity and the bantering humour of the dying crofter folk.

“John Guthrie himself got a gun, a second-hand thing he picked up in Stonehaven, a muzzleloader it was, and as he went by the Mill on the way to Blawearie Long Rob came out and saw it and cried Ay, man, I didn’t mind you were a veteran of the ’45. And father cried Losh, Rob, were you cheating folk at your Mill even then? for sometimes he could take a bit joke, except with his family.”

The author’s craft

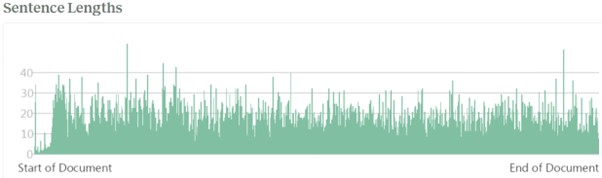

Grassic Gibbon uses several devices to achieve his effect. The main one is, undoubtedly, the use of the Doric Scots dialect of the northeast. In his hands, there is nothing of Walter Scott’s invention of a romantic Scotland. It is the real people of Scotland we hear, small minded, big-hearted, dreaming and dying. The language, of course, has a sad and lyrical music to it. And it also creates the illusion that we are part of a gossipy chat around a fireside, the true stream of consciousness of the narrators. This effect is strengthened by summary sentences that end many sections which begin “So that was how ….”

There are three narrators: an unnamed voice, Chris Guthrie herself, and Greek chorus of the whole gossiping community. And the telling uses a combination of first, second and third person. The use of the second person augments the conversational and confessional nature of the read: Chris is telling us how she feels and acts.

Deep time is another of his devices, creating the sense that this brief flickering and dying of the light of his cast of characters is part of a longer story of constant change. The Prelude sketches a huge antiquity that links Cospetric and his slaying of the gryphon through all the ages of Scotland from William Wallace’s rebellion against English occupation, through the Reformation and French Revolution and finally the clearances and on to the coming of John Guthrie and his family to the croft at Blawearie. And older still are the standing stones by the loch, the place of peace and safety to which Chris repairs in times of turmoil. Many of the chapters open and close at the standing stones.

A lyricism of nature pervades the detail of all the writing, with the call of the birds, the smell of the new-ploughed earth and the feel of the snow and the wind.

Grassic Gibbon frequently makes use of repetition:

“As the gnomons of a giant dial the shadows of the Standing Stones crept into the east, snipe called and called”

The effect of the repeated words is, at once, powerfully poetic and reassuringly conversational.

Character

The central character is Chris. And an extraordinary character she is, for a male author to have had such insight into the life and dreams and fears of a woman. Chris is strong and determined and fearful and doubting. The book opens with her dreaming of becoming a teacher. But this Chris fades and dies. She thinks of this one as the English Chris. When her mother commits suicide she becomes the second Chris, the Scots Chris of the land who must tend to the house. Released by the death of her sour and abusive father, the third Chris is claimed by that coarse tink Ewan Tavendale:

“He looked over young for the coarse, dour brute folk said he was, like a wild cat, strong and quick, she half-liked his face and half-hated it”

Ewan loves and marries her and then, gone for a soldier in the First World War, returns and ill uses her before being shot as a deserter. Though there is love, it is a love as clear-sighted and hard-headed as the folk of Kinraddie.

“She felt neither gladness nor pain, only dazed, as though running in the fields with Ewan she had struck against a great stone, body and legs and arms, and lay stunned and bruised, the running and the fine crying in the sweet air still on about her, Ewan running free and careless still not knowing or heeding the thing she had met. The days of love and holidaying and the foolishness of kisses–they might be for him yet but never the same for her, dreams were fulfilled and their days put by, the hills climbed still to sunset but her heart might climb with them never again and long for to-morrow, the night still her own. No night would she ever be her own again, in her body the seed of that pleasure she had sown with Ewan burgeoning and growing, dark, in the warmth below her heart. And Chris Guthrie crept out from the place below the beech trees where Chris Tavendale lay and went wandering off into the waiting quiet of the afternoon, Chris Tavendale heard her go, and she came back to Blawearie never again.

… Turning to look at him, suddenly Chris knew that she hated him, standing there with the health in his face, clear of eyes–every day they grew clearer here in the parks he loved and thought of noon, morning and night; that, and the tending to beasts and the grooming of horses, herself to warm him at night and set him his meat by day. What are you glowering for? he asked, and she spoke then at last, calmly and thinly, For God’s sake don’t deave me. Must you aye be an old wife and come trailing after me wherever I go?”

None of these Chrises are offered by the widow Chris Tavendale to her new husband, the Reverend Robert Colquohoun, who spirits her from Kinraddie and into the next book of the trilogy, Cloud Howe.

Though Colquohoun appears in the book only at the end, it is his voice, giving the dedication to the fallen of the place, that words Grassic Gibbon’s meaning.

“Nothing, it has been said, is true but change, nothing abides, and here in Kinraddie where we watch the building of those little prides and those little fortunes on the ruins of the little farms we must give heed that these also do not abide, that a new spirit shall come to the land with the greater herd and the great machines.

For greed of place and possession and great estate those four had little head, the kindness of friends and the warmth of toil and the peace of rest–they asked no more from God or man, and no less would they endure.

So, lest we shame them, let us believe that the new oppressions and foolish greeds are no more than mists that pass. They died for a world that is past, these men, but they did not die for this that we seem to inherit. Beyond it and us there shines a greater hope and a newer world, undreamt when these four died. But need we doubt which side the battle they would range themselves did they live to-day, need we doubt the answer they cry to us even now, the four of them, from the places of the sunset?”

It is a testament to the greatness of the book that I find myself dreaming in Kinraddie, and its rich vocabulary coming, unsummoned, to my tongue. And the word that comes to mind is “blithe”. It’s a blithe book and no mistake.