Let me get the answer out of the way right from the top—no, of course not. George Orwell said, “No book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.” Our lives are political, so what we write is also political. Even fairy tales are political. If storytelling wasn’t political, tyrants wouldn’t trouble to ban or burn books.

What does political mean?

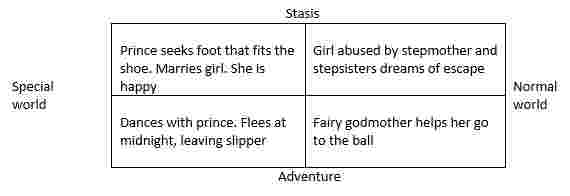

So, next, a definition. I don’t mean political with a small “p”, party politics, though some stories may legitimately be about such partisanship. I mean political with a capital “P”—the way power is distributed and how it affects everyday life. If a character doesn’t have enough to eat and must choose between paying the rent and buying school kit, that is a political context. If a character is saved from domestic drudgery by a prince, that too is political.

Breaking writing rules

But doesn’t this cut across so many writing rules? Literature, after all, is art, not propaganda. Readers don’t want to be yelled at or told what to think.

Yes, fiction writing isn’t propaganda, or political science, or journalism. But this doesn’t mean fiction doesn’t deal with politics. It just deals differently with the subject. Fiction makes political situations personal.

Characters makes us care

Fiction is about character. Even in plot-driven stories, it’s the characters who make us care. A story in which the characters are simply vehicles for a political argument would be dull. The politics of Orwell’s 1984 isn’t particular subtle or nuanced. It’s the plight of Winston Smith that engages us. There’s nothing special about the role of politics here. This is not different than any other over-indulgence in plot or theme. If the characters spend the whole story blowing each other away or discussing particle physics, it would be equally dull.

Characters live in three circles. They have an inner life and a circle of intimates, friends and colleagues. But they also have a third circle—the social setting that defines their concerns, their view of the world, and their beliefs. Ideology is a strong determinant of the third circle.

Readers don’t like being told what to think

You get this comment a lot in discussions about political fiction. And, when you come to consider it, this is odd. Nobody ever complains they feel manipulated when a writer equips a character with some other trait like selfishness or courage. Writers devote a lot of care to telling readers what to think. They craft the characters to engage sympathy, structure the plot to create peaks and troughs of tension. So, maybe the principle is readers don’t like being told to think in ways that challenge their preconceptions. But isn’t that precisely what literature is supposed to do?

“Some people will suggest that dealing with themes is ‘didactic.’ Don’t be fooled. Those same writers will put themes in their own works, and usually they’re taking stands that oppose yours. For example, if you argue that morality is innate and central to what a human is, they’ll argue that it’s situational and we’re all just animals. They don’t oppose the idea of stories having themes; they may just be opposed to your views. So make sure that your arguments are rigorous and persuasive.”

David Farland How to Win Writing Contests and Big Publishing Contracts

We tend to notice ideology and feel we’re being preached at when the text departs from our unconscious biases about the world. There is a saying that the ideology of the powerful is the belief that their view isn’t ideological, just common sense. What makes an ideology work is that it articulates a lived sense of the world. One person’s common sense is another person’s propaganda. Readers who react with fury to having an ideological viewpoint thrust on them by authors rarely respond in a similar vein to, say, thrillers or romance. Yet both tend to have a fairly transparent ideology.

Thrillers typically pit a plucky hero against the forces of evil. Over time these forces have varied from the Nazis, the Soviet Union, Islamic fundamentalists, shadowy corporations, and elite cabals, depending on who the “enemy of the day” is. The politics goes unnoticed because it’s an assumption about the forces of good and evil shared between author and reader.

Less obviously, romance too contains an ideology about people and relationships. In the classic romance (consider Tristan and Isolde, Romeo and Juliet) love is a force that is stronger than human will, incompatible with everyday life, and its proper end is death. More contractual or rational bondings are out, as is working at a relationship.

Readers should be left to make up their own minds

This is the “writer as witness” idea and it’s really back to the “readers don’t like to be told what to think” argument. The notion is that the writer should present the facts and leave the reader to judge their meaning. And it’s an odd view, because it applies more to journalism than to fiction. Though, it has become such a truism among fiction writers that it tends to be said without question.

In reality, most of us writers don’t operate like this. The writer surreptitiously shapes the reader’s perceptions in a thousand subtle ways. How could the reader come to their own conclusion? We select the contents, we craft the order in which they’re displayed, we polish and shape in order to create the effect we desire. Creative writing describes events in the light of the ends we ordain for them. The open-endedness is an illusion. Of course, no two readers ever render exactly the same story in their minds, I accept that. They may even disagree with our conclusions, depending on their own concerns and life experiences. Even so the writer is not only witness and advocate but also judge and jury.

Everything reflects an ideology

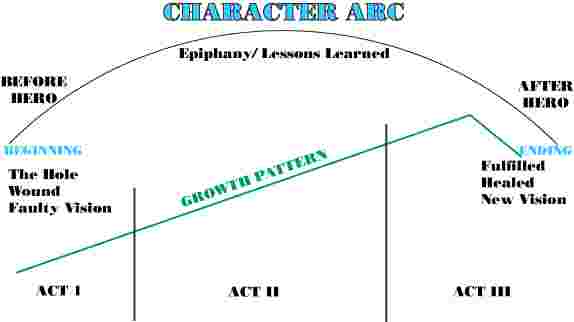

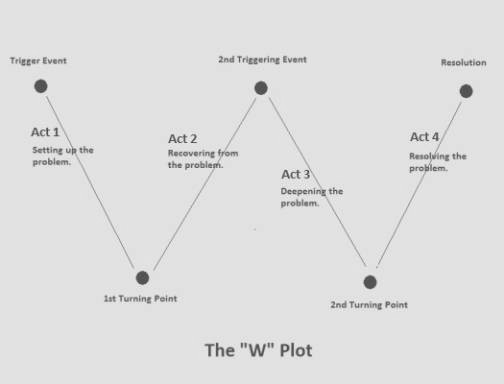

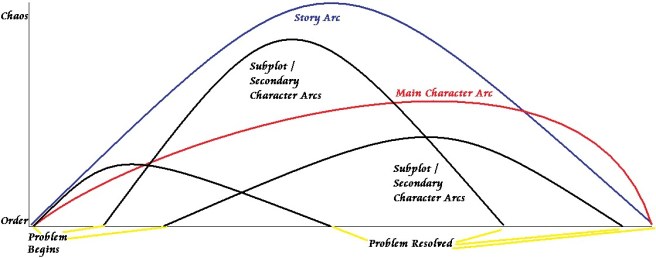

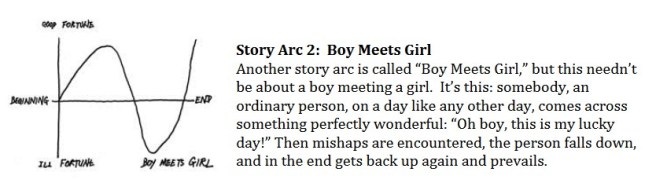

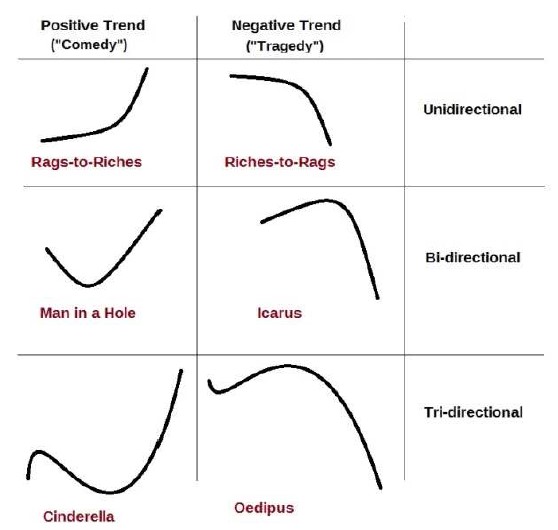

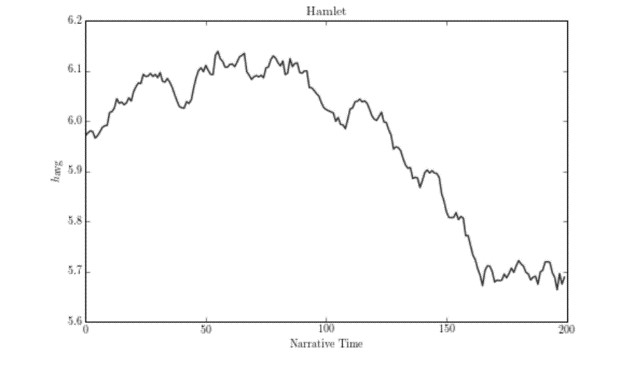

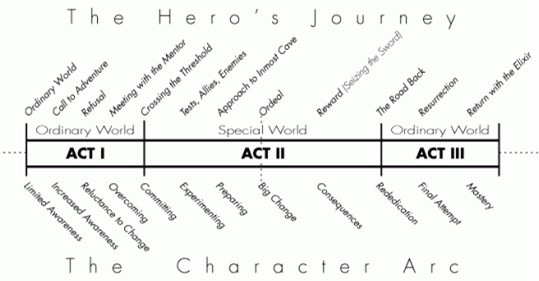

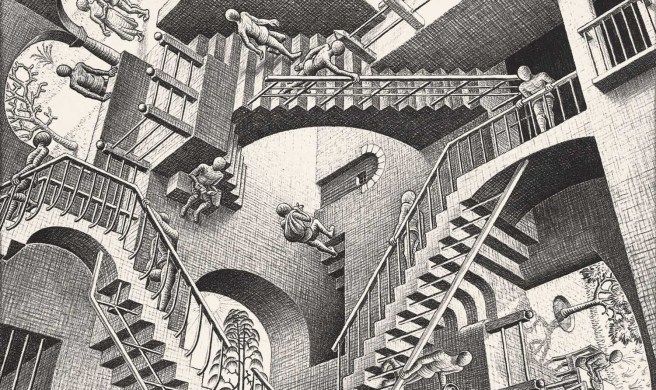

What could be more natural than a fictional world with protagonists and villains in which characters undergo an arc of change? This is, surely, the ABC of how to write a story. And yet this too is a product of a particular (wealthy and individualistic) social order. There are literary traditions in other cultures that use very different conventions. I argued in an earlier blogpost:

There is a view of the person and of development contained within these formulae.

- We are individuals

- We choose our own fate and can change

These principles of character arc seem so obvious we hardly even notice them as assumptions. But they come from a particular kind of society and, to other cultural traditions, they are far from obvious. How about these propositions:

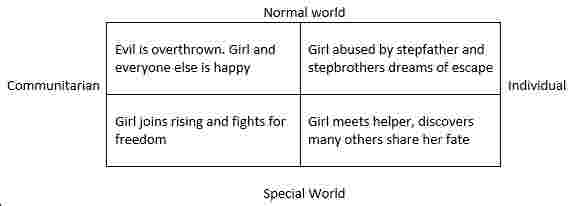

- People become people through other people. This is the core principle of the Ubuntu cultures of Southern Africa. In other words, humanity is a quality we owe each other. Or, in the European tradition, John Donne’s famous “no man is an island”.

- The number of people on the planet who can choose their own fate is extremely limited. The starting conditions of wealth, gender, race, status and caste circumscribe our choices. For many people, change is unthinkable. Those who do escape their circumstances are not representative of their peers.

These differences are not only narrative, but moral. The first principles are individualistic, the second communitarian.