I have a new goal as an author – writing gracefully. This goal arrived by accident. I came across the magazine Metaphorosis (“intelligent, beautifully written stories for adults”), whose editor has posted a helpful description on their website of what they’re looking for. He writes of quality prose “it’s not a question of adornment, but of grace”, and cautions against going overboard with images and metaphors. I wonder if I might be in danger of writing without grace.

My journey as a writer

First successes as a writer came in 2015. My initial publication was a short sci-fi story about time travel and the grandfather paradox. Two other stories were accepted that year.

In the years before my breakthrough, I had submitted eight stories. But, though I didn’t know it at the time, the magazines I contacted accept on average only 0.82% of what they received. Well beyond my ability level

The big change from previous years was (a) my writing was improving, and (b) I was more targeted about where I sent my stories. .

In 2015, I was much more realistic, submitting 23 stories to journals which had an average acceptance rate of 16.99%. The publication I was most proud of was a slipstream story, Zhuang Zhu’s Dream, published in Gold Dust, which then accepted 6.67% of the material sent to it. Last year, my greatest achievement was the story Interstices, published in Structo, which then accepted 3.85% of submissions. You can read both stories by clicking on the links on the sidebar. Two other pieces were also accepted in 2016.

This year, I’ve been more adventurous. So far, I’ve submitted 14 stories to magazines which have an average acceptance rate of 3.15%. I’ve had one story accepted since January. And yet I wondered if my writing had really improved enough to merit targeting more difficult publications.

Starting simple

When I look back at what I was writing before I got published, I can certainly see a change. As a teenager I wrote stories. One was even submitted to a magazine and rejected. I wish I still had that rejection slip – it would have been revealing. Hazily I remember it as saying something like “nice idea but needs more work”.

In 2011, I joined a local writers’ group, a diverse bunch of novelists, poets, and authors of short-stories. Later I also linked up with an online writing community. My apprenticeship to fiction began. Both groups were really helpful in critiquing and improving my work. I learned and practised many of the basic craft skills of structure, character, point of view, and, of course, grammar. I discovered that I already had a natural facility with wordcraft, perhaps based on an adolescent foundation of intense poetry scribbling.

The stories I was writing then are much simpler than my current stuff. They are generally built around a single idea, written with beginning, middle and end. The end is often a twist. Here’s one from that period:

For the first time ever, the August temperature hit 42 degrees. John Campell leaned his head against the aircon-cooled window of the Maglev shuttle as it ran parallel with the freeway and looked at the empty cracking asphalt. It was cars he missed most. At 21, so many years ago, that metallic blue Tigra had been his power and his freedom. His grandchildren didn’t miss cars at all. As the elevated track crossed the causeway over tidally sodden land he looked down at the empty places where he used to walk, go to school, and play. And soon the city came into view, its silver SmartPaint dazzling in the 42-degree late afternoon sun.

How he wished it hadn’t been him; that he hadn’t been born, when he was, in 1990. Born to pass through what the media now dubbed “the bottleneck”, when everything changed. How he wished it wasn’t his generation that was paying the price for mending the planet. After the It had taken a tough alliance between the Moralez administration in the US and the Fanoniste governments abroad to create a blueprint a frightened and reluctant world would follow.

Still there was money to be made out of saving the planet. And GaeiaTek was making its share. He transferred from the shuttle to a company bike and made his way to the conference room. As he pedalled, he rehearsed his presentation on algal seeding for carbon sequestration off the Ecuador coast

.Was this simplicity the essence of grace?

Experimentation and growth

Around 2014 I began to experiment. In one story, for example, I tried to describe the same event from the point of view of two different protagonists. I also explored more complex, and not necessarily likeable, characters, and to read more adventurously. My first whimsical experiments with what you might call fabulism and slipstream originate from this period.

Slipstream is a kind of non-realistic fiction that crosses conventional genre boundaries between science fiction, fantasy, and literary fiction.

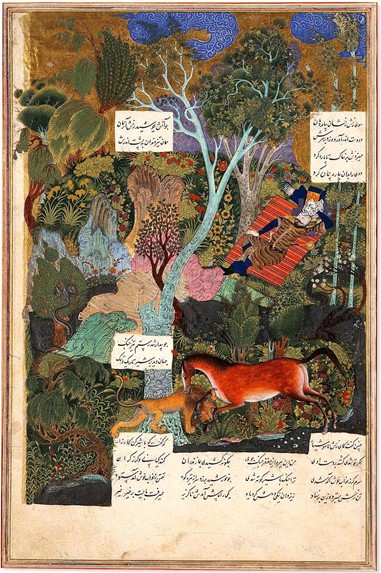

Fabulism is the intrusion of fantastical and mythological elements into a realistic setting.

The slipstream probably originates from a childhood fed by science fiction. The fabulism derives from my lifelong fascination with myth. There’s a particular sensation I have when I write this kind of story – I can feel the air blowing free and wild, and writing it is a guilty pleasure. It always feels like something I’m doing just for fun. And I never think they’re really “serious” until I’ve put them away in my bottom drawer and let them germinate. The tale I published in this genre, Interstices, was first drafted in 2014. Oddly, my science fiction and fabulist stories have been the most successful. Four of my seven publications are in those categories. Yet it’s my socially-grounded writing that I consider more important, though only one of them has so far been published.

The next big change, in 2015, the year I got published, was triggered by joining the University of Iowa Writers Programme MOOC (Massive Open Online Course). I’ve already blogged about what I learned from this so I won’t cover it again. I was resistant to this change at first because it was a turn to more complex literary writing. Literary fiction had always seemed rarefied and elitist. And yet I’m drawn to complexity, to layers in stories, and to motifs that repeat. The earlier work travelled in too much of a straight line from start to end. This made the tales “flat”.

I discovered the writer can forge a sense of deeper meaning and immersion through the artifice of repetition and by having different characters, situations and timelines echo and resonate with each other. Chains of words can create the illusion of causal connection or bridges between elements that are, in the prosaic world, distinct and incommensurable.

A tutor in the University of Iowa MOOC told me “If we are just worried about the pieces to make the events line up for some big climactic moment, then we might not be paying attention to building a world that is primed for resonances, for moments that, when plucked, make other moments spring back to life, thereby creating vibrations across the entire narrative world.”

To illustrate what I mean about layers of complexity, this is a diagram I drew to help plan the plot threads for a story, Short Circuit, I’m currently working on:

The setting is the Abbey of Lindisfarne at the time of the Viking raid in the year 793. The green line traces the life of the protagonist, a monk called Billfrith, who is illuminating a manuscript for the King of Northumbria. Woven through this life are abrupt changes, short-circuits, which have to do with a tension between construction and destruction. Billfrith associates the destruction with iron and his old life as a blacksmith’s apprentice; and the construction with the knowledge his current contemplative life in the Abbey allows him to develop. There is another text which captures his attention, describing alchemical experiments. He experiences a revelation just before the attack forces him to confront his past and drives him to desperation. Motifs of iron and fire are woven throughout the story.

So my writing has definitely changed. But is it better?

The challenge of grace – back to simplicity?

The post on the Metaphorosis website offers very useful detail about what an editor is looking for: a strong opening, quality prose, and a satisfying and appropriate ending. Quality prose, the editor says, often works on two levels at once. So I’m on the right lines there. Other major reasons for rejection are:

- Awkward backstory, info-dump

- Grammar

- Character not credible or distant

- No story/resolution. “A surprising number of stories don’t have enough story to them. That is, they’re slice-of-life pieces, or vignettes, or for some other reason add up to ‘So what?’”

I’m pretty confident I’ve learned how to do all of those things. But the editor’s stricture that quality prose is “not a question of adornment, but of grace” rang a warning bell. Was this me? An overly-literary fascination with complexity? Certainly, some of my readers have warned me against big words and subtle turns.

Yeats once expressed his aim as being to “think like a wise man but communicate in the language of the people.” I applaud that aim. I was reminded of the subtle power of simplicity recently reading the gorgeous Palm of the Hand Stories by Yasunari Kawabate. In his 1968 Nobel Prize lecture Kawabata said, referring to Japanese art, “The heart of the ink painting is in space, abbreviation, what is left undrawn.” His writing is as spare as a Zen drawing. For example, this description from his story Thunder in Autumn: “It was early autumn, when the young girls returned from the sea and went walking about the town like fine chestnut horses”.

One of the forms I enjoy writing is very short 100-word flash fiction. This enforces that Zen discipline of using what’s left unsaid. I wonder if maybe I should apply the same discipline to my longer works. Deciding that the only way to test whether I write with grace was to submit something to Metaphorosis, which has a 2.4% acceptance rate, I was rejected.

Please let me know what you think.

Please let me know what you think.