Stories are among our oldest cultural creations. They tell us what’s important and what’s unimportant; what goes with what; who to praise and who to blame.

Stories are different from real-life events. Real life is lived forwards with unknowable endings, whereas the meaning of stories is inferred backwards: stories are about events in the light of their endings. A good ending, it is said, should have the effect of being inevitable and yet surprising.

Character

We may be intrigued by plot, but it is characters we fall in love with. In many ways, character is at the heart of storytelling. When you have a character with a want, you already have the beginnings of a plot. When you have another character with an opposing want, you have drama.

Authors create characters in many ways. By far the most common, and the least interesting is to resort to archetypes. There are many different notions of who the archetypal characters are, but what they all have in common is the reassurance that we already know everything about them. They will not surprise us.

Better, much better, is a full, rich, complex, and contradictory character. Such characters create the illusion of being real people. Though, as Nobel Prize winning author Orhan Pamuk argues, real people do not have as much character as is found in novels.

Plot and story

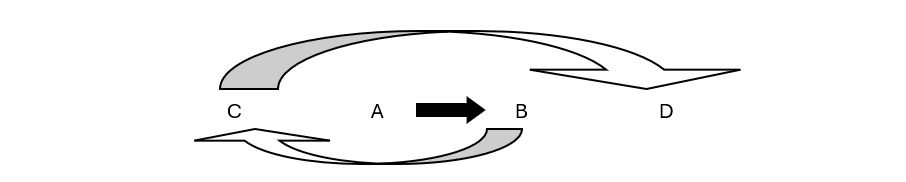

Some definitions are advisable here. A story and a plot are different things. Plot is the time sequence of events, their causes and effects. But the plot may be told in different ways. If the events of a plot are A, B, C and D, they may be told in this order.

But they may also be told out of time sequence. For example, the telling may begin with C and then flash back to A and B before revealing the dénouement at D.

Plot is the time sequence of events. Story is the way those events are recounted. A poor plot can be saved by clever storytelling.

Of course, the telling of a story is much more than this. Vocabulary, sentence structure, pacing, voice, and many other things go into the making of a story.

Narrative

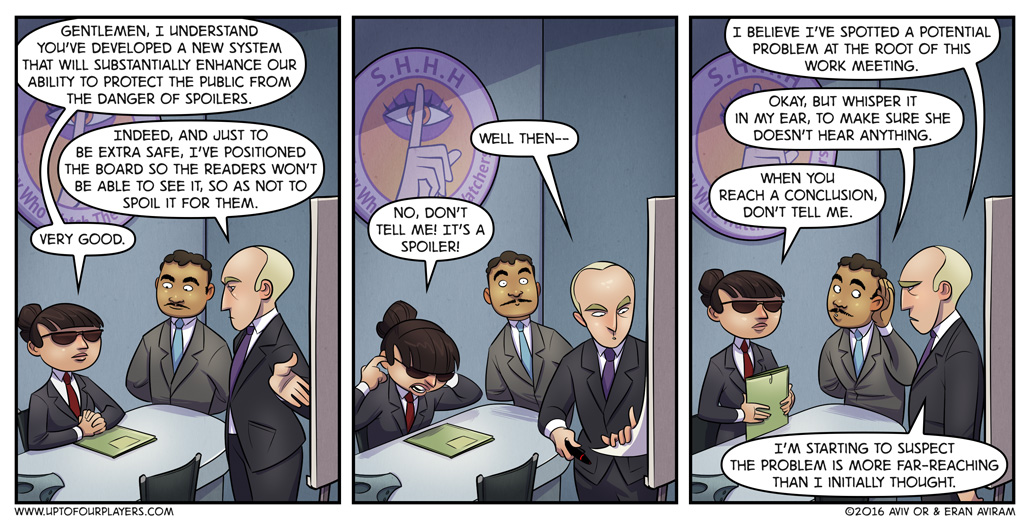

A third definition, in addition to plot and story, may be important. I will call this narrative, to distinguish it from the first two. A narrative exists when it leaves the author’s head and enters the heads of readers or listeners. The reception of the tale is simple passive process. The listener or reader actively collaborates in imagining the setting, the characters, their actions and what these all mean. There are as many narrative variants of a single story as there are listeners. Some of these variants may be significantly different from the author’s intention.

An author may say that they can’t control how an audience responds to their work. And that is true. But an author can anticipate some likely responses and misunderstandings.

Layers, Symbols and Meaning

Layering refers to the hidden depths of a story. This depth can make all the difference between a work that chugs along satisfactorily and one that stays in the reader’s memory for long after the last page is turned. There are different kinds of layers. For simplicity, I’ll categorise them into three types:

- Story layers. A layered story has more than one plotline. For example, Elif Shafak’s ambitious novel There are Rivers in the Sky attempts to braid three timelines: ancient Mesopotamia, Victorian London, and the present day. She does this by alternating chapters. Of course, in the end, a story of this type must bring all the subplots together at the end. To repeat, stories are events in the light of their endings.

- Character layers. In modern Western writing, the plot is generally driven by the protagonist’s desire for something (their want). More interesting and deeply-crafted characters have layered depths though. Often, the protagonist’s want may be in conflict with their true need. Katiniss in Suzanne Collins’ The Hunger Games, for example, wants to win the Games at any cost, but what she truly needs is to learn to sacrifice herself to preserve her own autonomy. The reader’s experience of redemption comes from the protagonist recognising what their true need is and finding completion.

- Symbolic layers. This is perhaps the most literary of the layering types. The things that happen on the surface have an additional symbolic meaning. The trick of authors who do this well is not to hit the reader over the head with the meaning, but rather to allow them to find the meaning themselves. Once found, this meaning illuminates the whole story. A classic example here is the theme of unachievability in F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby. Many elements are knitted together to underscore this theme. There is, of course, Gatsby’s unrequited love for Daisy, the endless parade of motor cars, and the recurring symbol of the green light across the bay. Fitzgerald intends this symbolic layer to capture the destruction of the American Dream.

Putting together a story

Characters with multiple dimensions. Stories that achieve the most intriguing telling of their plot. Tales that carry layers of meaning, making the story resonate with deeper issues. These are the elements of good story-telling, stories that can make their way into the world as narratives which reverberate with the sympathy and questioning for readers.