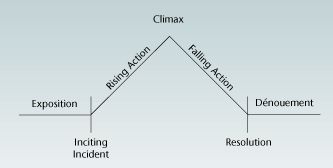

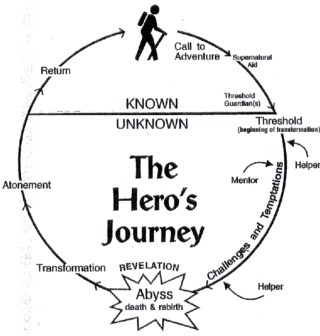

Tale the First. In which Cara is apprenticed to Pasco

As you know, Cara was born just after the devils came. But she understood no other world and was, like all children, accepting of everything and of nothing.

Even as a young girl, she would ask many questions. ‘Where did we come from?’ and ‘Why are we here?’

She asked so many questions that, in the end, her parents ran out of answers. When Cara had reached three hands of summers, her mother decided to leave their village and take her to Chucanchu to foster her with old Pasco. He was a great Makar, who could teach her the answers, and the rhyme and metre for reciting them.

At the gates of the city, Cara saw devils for the first time, a pair standing sentry. They had eyes like people, but she dared not meet their gaze for their bodies glittered in the sun. She pressed close to her mother. But after the guards allowed them to pass, she looked back in curiosity. And then she stared at everything, turning to left and right. Though Chucanchu is not the greatest of our cities Cara knew only her village. She was astounded by the thronging streets, the busy markets, and the great buildings.

Her parents left her, and she was not afraid.

Cara plied Pasco with all the questions that had been dammed up like a river behind a beaver lodge. She asked, ‘where did we come from?’ and the Makar said ‘that is a good question and I will tell you.’

He said, with mischief in his nut-brown eyes, ‘We came from our mothers.’

‘Yes, I know this, but where did they come from?’

‘Why, they came from their mothers.’

Cara stamped her foot. ‘I mean where did everything come from?’

‘Now that is a deeper question, child, and I will tell you, so listen well. Everything came from nothing, and to nothing it will return at the end of days.’

‘That makes no sense,’ said the girl. ‘How can everything come from nothing?’

‘Makes no sense, you say? But did you not come from nothing? Until you were born, you did not exist.’

Cara had to agree, and Pasco continued.

‘Some people say that everything grew in a great gout of fire, but others say it cannot be so. For we know fire cannot burn without air. And, furthermore, air fills all of a lodge at once, from one end to another. So, I, and many others, hold that air came first, and the world was born in a huge rush of wind, though I was not there. Air is the mother of everything, I believe.’

‘So if only air and wind existed, where did all the other things come from?’ asked Cara. ‘How did the land and sea and the mountains arise?’

‘The sea was made next. In the air, clouds gathered and grew dark, and rain fell. It fell for more days than we have counting words to name, until above was the air, and below was the water, though I was not there.’

‘And how then came the land, and animals, and people?’ asked Cara, breathlessly excited at what she was learning.

‘Patience, child,’ laughed the old Makar. ‘The world was a long time a-making, and its tale must needs be a long time a-telling. As air is the mother of everything, so fire is the mother of the world. At the bottom of the water, fire grew.’

‘But how can that be? Water puts out fire.’

‘That is only the fire we poor mortals have. Yet there exists another fire, purer, hotter, that lives in the deeps. Have you not seen the mountains that smoke and belch forth, and the scalding water that hisses from fissures? Does rain extinguish that fire? Does the sea put out the blaze when land rises from the waters? That is the original inferno of the deep. The fire gathered there, building and growing. And at last it rushed forth, up through the sea and high into the air. As it cooled, it solidified, and so the world was created, though I was not there.’

‘And people? How did they come?’

‘To understand people, I must first tell you about Crow,’ Pasco replied. ‘In the beginning was Crow. There was not form upon the world, nor creatures upon the land, and only Crow’s wings stirred the air.

‘Crow was lonely. So he brought form and shape to the earth. He retched, and from the earth’s belly beasts emerged, swarming, swimming, and walking each according to their type. In his efforts, he dug out a great mass of gold which he flung into the sky, and she became the sun. Then a great mass of silver, and he became the moon.

‘But still Crow was lonely. So he played a trick on the earth. In his beak, he held a shiny smooth pebble, round as the sun and smooth as a lake. The earth wanted the shiny thing and grew a hand to grasp it. Quick as a flash, Crow dropped the pebble and seized the hand’s wrist, pulling until the hand stretched into an arm. Twisting the arm, he forced it to rise from the mud, making a head and torso. The mud grew legs, sat up, looked around, and said, “Amazing, Crow. What a splendid world you have made. I could never have done this.” Crow was content and placed the pebble into its hand. From the mud came men and women, though I was not there.’

Pasco went on to tell her of Crow’s mischief, but that is another tale, and you already know it, as every child does.

Tale the Second. In which Cara asks about the Coming of the Devils

‘Tell me of the coming of the devils,’ demanded Cara. ‘I saw their eyes.’

………….

To read the rest of Cara’s Saga and how she learned to sing the knots that bind the world, download it for free by clicking the button on the right