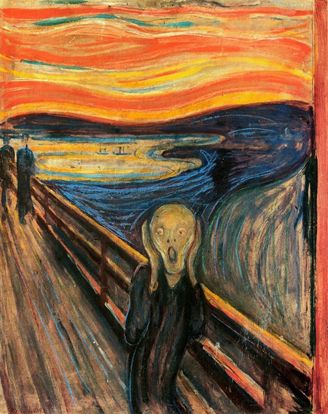

They say write about what you know about. And that’s good advice. But your characters are slippery little eels. They start to live lives of their own and do things you’ve never experienced. I had this difficulty with Reuven, the everyman character in my novel A Prize of Sovereigns. In this week’s serialised chapter published on Wednesday, he returns from war, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. I have never been to war, though I have worked in conflict zones. I have never suffered from post-traumatic stress. How was I going to write that?

Research, of course, is the answer. I read extensively, both clinical accounts and memoirs of war induced stress. Reuven suffers most of the standard symptoms, which are, as listed on a veterans’ website:

- Feeling upset by things that remind you of what happened

- Having nightmares, vivid memories, or flashbacks of the event that make you feel like it’s happening all over again

- Feeling emotionally cut off from others

- Feeling numb or losing interest in things you used to care about

- Becoming depressed

- Thinking that you are always in danger

- Feeling anxious, jittery, or irritated

- Experiencing a sense of panic that something bad is about to happen

- Having difficulty sleeping

- Having trouble keeping your mind on one thing

- Having a hard time relating to and getting along with your spouse, family, or friends

Plus, Reuven is prone to taking excessive risks.

Apart from research, the big help was writing the chapter not from Reuven’s point of view, but that of his wife, Jyoti (though an earlier chapter takes Reuven’s point of view).

“The man who came back from the war to Jyoti the second time stumbled to a broken rhythm. He limped on a stick. He found it difficult to grasp things with the remaining two fingers of his right hand. He could not hold a mattock or a hoe so easily anymore, and fieldwork came hard to him. Swinging a scythe was near to impossible. It wasn’t just his amputated fingers that made a scythe impossible. His broken ribs had healed wrong, and when he swung his body, the pain in his side was as if the scythe was cutting through his own flesh, not the hay. Jyoti had to do the hay-making for him.

But this was not the thing that troubled Jyoti most. Something was broken inside her man. He started at sounds. In any room he insisted on positioning himself with his back to the wall, facing the door. He would say with a laugh that this was so nobody could sneak up on him. But Jyoti did not think he was joking. He was alert the whole time to dangers that only he perceived, as if he was still at war.”

Writing from Jyoti’s point of view simplified the problem. This is Reuven, as she sees him. She suffers because he is withdrawn and snaps at her. She blames herself. And then one night he confesses the incident that is at the root of his self-loathing. He has still not told her everything that the reader already knows – not about the battles, nor about his fear of what he might do, nor still yet about his pathological risk-taking.

It’s through Reuven that we see the excitement of war. “For common folk like us, war is exciting,” he tells Jyoti . “You can do anything, take anything. It felt like I had some power.” And, it is through Reuven that we see the cost of war.