We were sitting on a porch in the middle of Mozambique, sharing a bottle of whiskey.

“The trouble with you Anglo-Saxons,” my Portuguese friend, Joao, said, “is that you only know one way of being.”

Portuguese has two verbs to be – ser, to be permanently, and estar, to be temporarily. Joao argued that understanding this difference affects how you are in the world. The ability to name something carries with it the power to recognise it, to feel it, to explore it. Words don’t just communicate meaning, they create meaning.

I was reminded of this conversation this week, when by chance I read three different articles about words. Tiffany Watt Smith writes in New Scientist about the way words may rewire our brains. The BBC website covers the achievements of the Historical Thesaurus of Scots. And I am in the middle of reading Helen Macdonald’s magnificent H is for Hawk, which is filled with the ancient and arcane vocabulary of falconry.

Tiffany Watt Smith, writing in New Scientist, argues that if we don’t have a word for a thing or an emotion, we may not recognise it. She speculates that the Machiguenga people of Peru, who have no word for “worry”, may not feel the emotion. Equally, she says, English speakers lack a word for awumbuk. This word from the Baining people of Papua New Guinea, describes the empty feeling after visitors depart. They believe departing visitors shed a heaviness into the air in order to be able to travel lightly. This heaviness lingers for three days and creates an inertia that prevents the hosts’ ability to tend to their home and crops. The Baining deal with this by filling a bowl with water to absorb the miasma overnight. Early next morning they throw the water into the trees, and normal life resumes.

Watt Smith suggests that language and culture influence what we see and feel by allowing us to link our sensations to a network of other associations, making it easier to seek out experiences which are consistent with this, and to filter out those which aren’t.

An old favourite example of my own is the Portuguese word saudade. This had no precise equivalent in English, and describes the pleasure of feeling sad. So well recognised is this emotion in Portugal that it has spawned a whole culture of music, fado, which you listen to in fado cafes so as to experience saudade. I wrote this description in an attempt to capture the emotion.

The evening air held onto the warmth of the day, but the light had a dying mellowness, full of shadows. It had a softness that contrasted with the harsh angularities of noon. I sipped gently. The wine’s tart greenness contrasted with the dark wood of the tavern, polished by an antique cargo of a hundred thousand nights of convivial transgression. The guitarist took his seat and tuned his strings, while the fadista, her eyes fixed on some spot beyond our prosaic gaze, composed herself. As the plaintive call of the fado rose, shrill and bright, other patrons drifted in from the sun-warmed cobbled lanes of the Bairro Alto, like leaves collected by an autumn breeze.

Strangers, we sat, communing together through the mournful power of the music. The air was suddenly crisper, the wine more piquant, my heart fuller as she sang of the doomed love between a Count and a street girl. I thought of home. When she finished, there was a moment’s pause, and then an outburst of applause. Most of us clapped, but the man at the table next to me coughed, the traditional form of appreciation in the Coimbra school of fado. The Portuguese have a word, saudade. It means the pleasure of feeling sad. I savoured, for the first time, the pleasure of feeling sad.

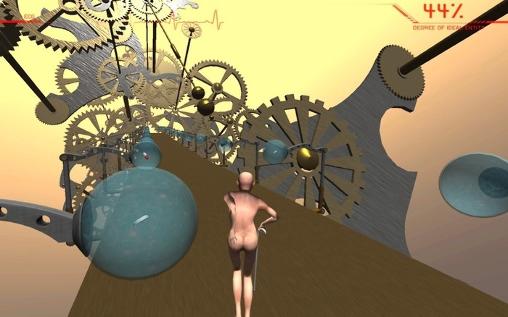

Music and dance may be the languages in which we communicate concepts and emotions for which we have no words. It’s also worth remembering that the ancient Greeks distinguished between six different kinds of love, where in English we have only the one inadequate word. Precisely distinguishing varieties of things is important when you live on the edge of survival. It turns out from the Historical Thesaurus of Scots that Scots has 421 different words for snow. In a country where weather can be swift and treacherous, being able to communicate precisely about conditions had survival value. Even today, when British trains in winter are halted by “the wrong kind of snow”, this precision may be important.

Some of the 421 words for snow

Pre-snow conditions (Gramshoch)

To begin to snow (frog)

To snow or sleet lightly (scowder, skiff, sneesl)

To snow heavily (onding)

A swirl of snow (feefle)

Snowflake (flicht)

Large snowflake (flukra, skelf)

Slush/ sleet (snaw-bree, slibber, grue)

A sprinkling of snow (skirvin, glaister)

A slight fall of snow (skirlin, flaffin)

A heavy fall of snow (hog-reek, ondingin)

Snow driven by wind/ movement of snow (spindrift, hurl)

Slippery snow (shurl)

A cover of snow (goor, straik)

Words are talismans – they have the power to summon. At the whim of the writer, they may summon demons or angels. Nothing illustrates this more powerfully than Helen Macdonald’s searing memoir, H is for Hawk, in which she describes with stark honesty how she coped with the grief of her father’s death by training the most dangerous of raptors, a Goshawk. Her hawk, Mabel, is “thirty ounces of death in a feathered jacket”. Her use of language is superb, rendering her grief, the “manning” of Mabel, and the minute details of nature with a unique mixture of poetry and science. Her prose offers the rare pleasure of words that make me go to the dictionary. And then there is the arcane language of falconry. There is the equipment of jesses and creances. When Mabel beats her wings and attempts to escape the perch, this is bating. When she enters the state of murderous desire to hunt, she is in yarak. I have already appropriated these words for my own.

Words give us more than one way of being. That is the writer’s craft.