We’ve all heard about stories within stories. But how about stories without (in the sense of outside) stories? I was prompted to consider this when I looked through the reviews of my novel, The Tears of Boabdil. On the surface, this is a story of an undercover cop, Vince, attempting to penetrate a suspected jihadi cell, and manipulating a target into a sexual relationship. It works as a thriller and as an (abusive) romance. And I wrote it so that it could be read that way. What struck me was that the majority of my reviewers gave it this reading.

There is also another possible reading: namely, that the thriller is simply a container for an exploration of what we mean by truth and lies.

The novel suggests that everything Vince believes he knows, including himself, is a story. The cop lives-out a cover-story. As his sanity fractures, the rules of his story world begin to permeate his real world. And that was what I was what really interested me in writing it. There are many clues and motifs that lead the reader to this question. But the narrative about truth, lies and stories isn’t told directly—it’s a conclusion the reader has to assemble in their own minds. I believe that reading is an active process involving both the reader and the writer, rather than the passive consumption of a story.

Beyond these two layers of the narrative, there are probably others, partially hidden to me, at least when I was writing it.

There’s a moral conclusion. Vince pays a price, a terrible price, for his deception. And his lover’s/victim’s life is devastated. No work of fiction can escape this moral (or ideological, if you will) dimension. Every story is built on a framework of beliefs about right and wrong. In comedy, the story is driven by characters mistaking each other’s intentions. In tragedy, characters struggle unsuccessfully against wickedness or with flaws in their own nature.

Perhaps there’s another layer, too. In rendering Vince’s mental collapse, I drew on mythology. He is increasingly beset by figures who represent his mother and his father.

The mother manifests as Ishtar, a Mesopotamian goddess, and the father as Malachi, who shares much in common with the ancient hero, Gilgamesh. These may not be simply decorative flourishes added by the author. I may be telling myself something about myself. I say this because I have again turned to mythology to render a major character in the novel I’m working on now. Mythological reference is powerful, not least because it imports through recognizable characters a cargo of other narratives. Perhaps I am drawn to the liminal deities of mythology because they allow me to say something about transgression across the borders between good and evil. Perhaps, I am exploring the idea that goodness is not quite as good as we like to believe, and evil not quite as evil. It is probably no accident that the other mythological character in The Tears of Boabdil is a trickster figure that often manifests as a crow. The lover/victim at one point says “Goodness is a solid whereas evil is a liquid. You need a little evil in you to weather the edges off the goodness, otherwise it cuts the heart.”

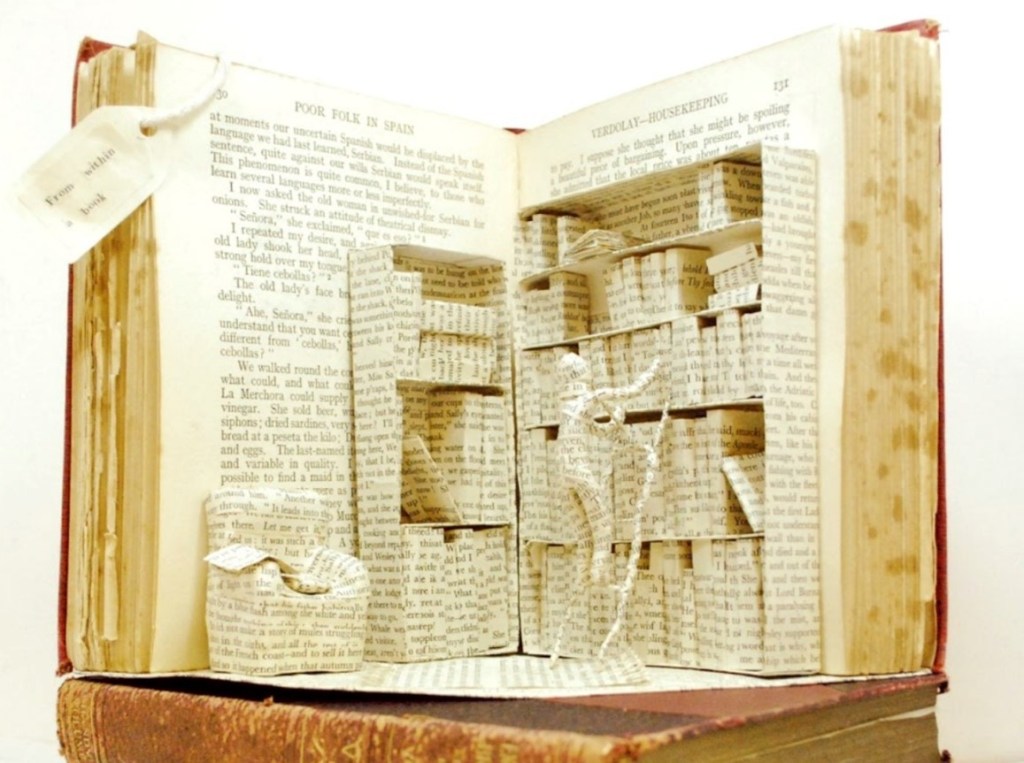

So, yes, stories carry fragments of other stories, other meanings, that invite the reader to put the pieces together in new patterns.